The first time I tried embroidery, it was out of desperation. I’d been trying to fill my workspace with more sex-positive artwork and, after hanging a piece from Elaro Embroidery that featured nude women with pink and red flowers in place of their vulvas, I fell in love with an embroidered uterus done by Elise of The Comptoir.

The only problem?

It wasn’t ready-made.

It was a damn kit.

I had to make it myself.

Now, I am a person who never learned to sew. My mother tried to teach me needlepoint when I was young, but I lost interest quickly. A friend taught me how to crochet when I was in my 20s, but I never quite got the hang of it. Now that I’m in my 40s, it is my husband who mends rips for me and sometimes even hems my pants. He is the one who sews badges onto our daughter’s Girl Scout sash and buttons onto blouses.

My god, though. I had to have this uterus. Even if it meant I had to do something I felt incapable of doing.

It took me over an hour to thread the needle my first time, and that was only because I found a needle threader in my husband’s sewing kit (which I immediately broke upon first use).

But after ordering a 24-pack of new needle threaders, I was officially in business. YouTube videos took me the rest of the way. By the time I’d successfully completed my uterus, I was hooked.

Since then, I’ve embroidered cats. I’ve embroidered inspirational phrases. I’ve embroidered the state of New Jersey. I’ve even embroidered a bookish self-portrait.

But what truly fascinates me is the use of embroidery as activism, even beyond the world of sex-positive activism.

A Super Brief History of Embroidery and Its Ties to Heteropatriarchal Femininity

For those who don’t know their knitting from their crocheting or their needlepoint from their cross-stitch, embroidery is a form of stitchwork used to decorate fabric or other materials. The word “embroidery” comes from the French word broderie, meaning “embellishment” and, according to several histories of the practice, can be traced back to 30,000 B.C.

Other examples of embroidery can be found throughout time and across the world, from China between the 5th and 3rd centuries B.C. to Sweden during the Viking Age. But it was at about the year 1000 that the practice of embroidery began to rise in Europe, with the ever-more-powerful Christian church and the royal families beginning to collect embroidered garments, wall hangings, and tablecloths as a show of their status and wealth.

Later on, in 18th-century England, embroidery became a skill developed by young girls to mark their passage into womanhood and their suitability for marriage. It wasn’t until the early 1900s that mail-order catalogs and pattern papers made embroidery more accessible to the wider population.

Embroidery: Tool of the Patriarchy or Source of Righteous Self-Expression?

Katherine Grayso writes for Harpy Magazine that, “[c]haracterised by a bowed head and lowered eyes, the very act [of embroidery] embodies traditional expectations of women: patience, silence and a focus on the domestic.”

She goes on to write that, as young women worked to develop the skill on their way to a hopefully well-matched marriage, the practice embodied characteristics such as modesty, obedience, and stillness… characteristics “reinforced by the religious samplers they’d often work from.”

Maybe this is what makes activist embroidery — the juxtaposition between disciplined and detailed needlework and phrases like “Feminist AF” — so delicious.

The term “craftivism” was coined in 2003 by knitter and activist Betsy Greer to describe the reclamation of traditional female hobbies such as needlework to advocate for social change. But craftivism was happening long before we came up with a clever term for it.

Journalist E. Tammy Kim writes for the New York Times that fabric arts such as embroidery tend to become more popular in times when women are feeling particularly pissed off. For years, women have stitched their messages onto large canvases, into hoops, onto tablecloths and clothing.

“To take up the needle,” she writes, “is to reclaim our histories of anonymous, poorly paid and unpaid female craft, garment labor and piece work.”

Kim also points out that because of its place within the domestic sphere, it can also be a refuge from the noise of the outside world, the things that make us angry and anxious, “a return to a female tradition when our bodies and minds feel so keenly under assault.”

I know that, for me, embroidery is a sort of meditation, something that requires my complete focus. In making my fabric taut within a new hoop, squinting as I knot and thread the needle, moving my hands through French knots and woven wheels, everything else falls away.

And then, something beautiful blossoms from nothing. Something beautiful and sometimes angry, too, all at once. Something that represents who I am and what I feel.

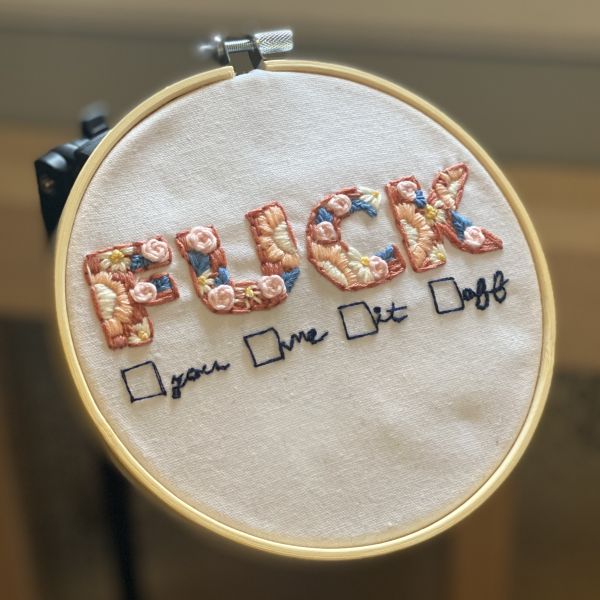

[The pattern below is from GetStitchDone.]

I love the story of activist Shannon Downey, who tweeted in 2017 that she was “so angry I’m stitching my damn protest sign just so I can stab something 3,000 times!”

That, to me, represents perfectly the visceral nature of creating a piece of artwork that carries a message of social justice. I love the act of embroidery as an act of creation and purpose and concentrated fury.

Since reading Aja Barber’s Consumed, I’m also starting to see stitchwork as a form of anti-capitalism, to see the possibility of using this new skill of mine to reinvent and repurpose the fast fashion purchases I regret and the pieces of apparel I’ve worn down to bits.

I have my eye on books like Noriko Misumi’s Joyful Mending and Katrina Rodabaugh’s Mending Matters.

How much more might my clothing matter to me if I had a hand in its maintenance and repair? I already adore this tank top I embroidered using a pattern from Olivia Skelhorne of RiverBirchThreads.

For more on embroidery as activism, I recommend reading Rozsika Parker’s The Subversive Stitch, Jen Hewett’s This Long Thread, and Betsy Greer’s Craftivism.

Follow These Brilliant Embroidery Artists on Instagram

Since getting into embroidery, I have filled my Insta feed with tons of brilliant artists who both inspire and intimidate me with their creativity and talent. Maybe they’ll inspire you, too?

Nneka Jones, for one, is a multidisciplinary artist who works in various media in service of social and environmental justice, but her embroidery portraits in particular — done using thread painting — are to die for. Here’s a piece from her Instagram feed:

Sheena Liam-Zacharevic is a woman whose work “explores the self, hair, and its proprietary role in womanhood and embroidery as a tool of quiet resistance.” I can’t get over the quiet artistry in these simple black outlines and the carefully styled braids:

I adore the way textile artist Victoria Villasana embroiders photographs, creating a collage-like work of activism:

I’ve been mildly obsessed with Sophia Narrett’s work ever since seeing a few of her pieces reproduced in A Woman’s Right to Pleasure. The unbridled sensuality and the playfulness exhibited in these pieces are downright stunning. I’m unable to embed her posts here, but click through to see “The Moment We Met.”

And to circle back around to my very first embroidery kit, Elise from The Comptoir plays around with the use of printed photographs much like Villasana does. I especially appreciate how accessible her work is to the average consumer. Her shop includes finished pieces, embroidery kits, patterns, and more.

Get Started with Your Own Activist Embroidery

And if you’re looking for kits and patterns to get you started, I basically spent a ton of time searching Etsy, but I’ll share some of my favorites:

Elise of The Comptoir, obvs

Theresa of GetStitchDoneDesigns

Sara Davey of pixelsandpurls

Miho of mipomipoHandmade

Dominique J. Chanel of NellyMakesEmbroidery

Hande of HoopatelierStore

Happy stitching, folks.