You may have noticed—in the time I’ve been writing for the Feminist Book Club—that I lean toward certain types of books. Sure, I enjoy memoir. I sometimes read sci-fi. I have a thing for comics and graphic novels. I have an entire shelf’s worth of narrative nonfiction about sex ed. But more than anything else, I love the creepy. The speculative. I love horror.

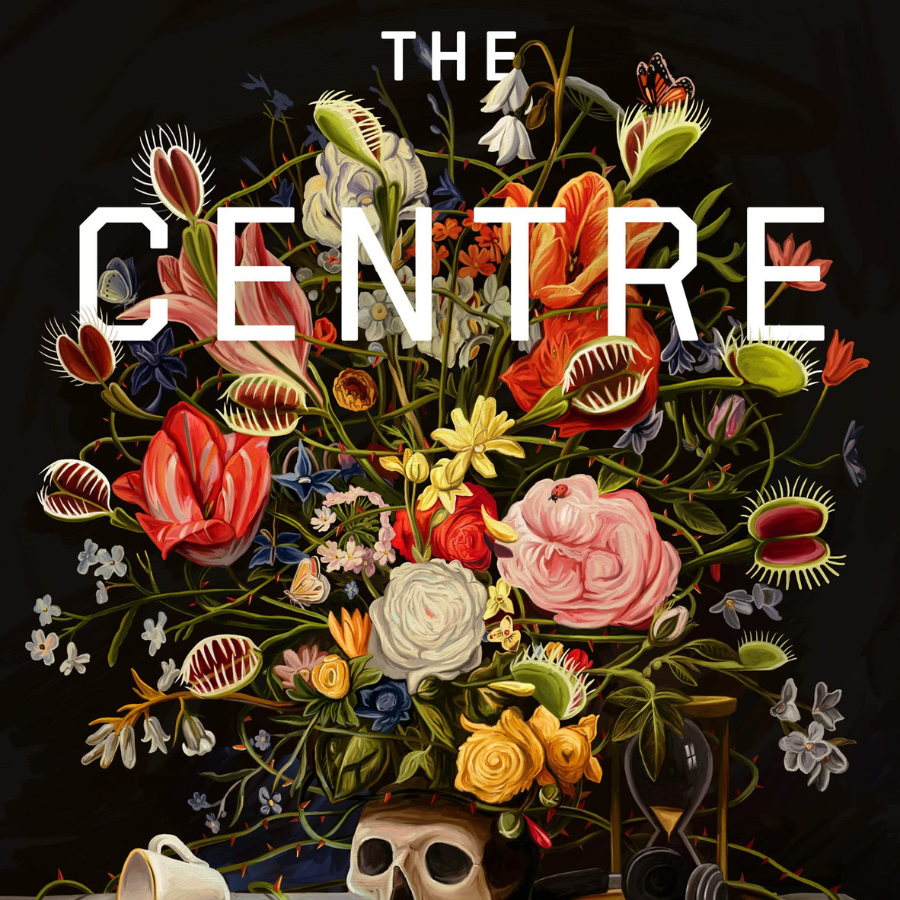

When a publicist reached out to me about Manazir Siddiqi’s The Centre, I was immediately drawn to its cover design, the focal point of which is a profusion of flowers and other plants, gorgeous blooms alongside thorny vines and toothy, gaping mouths. A skull sits in their shadow, in the midst of other desktop detritus. Color me intrigued.

The premise is just as intriguing. The protagonist, Anisa Elllahi, has dreams of being a translator of great works of literature. When she learns of a secret and super exclusive program that promises complete fluency in any language in just 10 days, she’s all in, no matter the cost. But the process is destabilizing and Anisa is plagued with troubling dreams and, over time, she becomes convinced that there is something sinister happening behind the scenes. Unfulfilled by the success she’s found in the wake of her time at The Centre, she wonders whether it was all worth it.

Sinking into the Story

When I first picked up the book, I’ll admit it: I wasn’t immediately drawn into the story. I found the voice (the book is narrated by the protagonist) to be odd, particularly with Anisa’s occasional asides to…well, I wasn’t sure. The reader? Toward the end of the book, readers learn more about the intention behind the narrative style but, up until that point, this breaking of the third wall happened infrequently enough that it tripped me up every time.

I also struggled with the likeability of the protagonist. This book explores questions of assimilation and appropriation (more on that below), an exploration I very much enjoyed. But because of Anisa’s relative levels of privilege and her self-centeredness, I questioned what the stakes were for her as a character.

Again, the intention behind the complexity of her character becomes clearer near the end of the book, when she is faced with quite the moral quandary. But for much of the book, I wondered whether she was the person I wanted to follow into the dark as the troubling secrets behind The Centre were eventually revealed.

Trying to Do Too Much?

Throughout the book, I also got the sense that Siddiqi—through her narrator—was trying to tackle ALL THE THINGS. There are clear, overarching themes that wend their way through the plot, forcing the reader to consider the politics of language and literary translation and, on a larger scale, assimilation and appropriation.

But Anisa also gets on her soapbox for a number of other issues. She ponders repeatedly the ways in which women are subsumed by their romantic relationships and, eventually, by marriage, allowing their own light to be dimmed. There is a bit of exposition on the devaluation of female friendships in comparison to the aforementioned romantic relationships. There are moments that glance at sexism in the professional realm, and the ways in which, so often, women prop up the men above them. There is also one scene that suddenly brings up questions around sexual harassment and power imbalances and consent.

All of these are issues I care deeply about. But the ways in which they were brought into the story sometimes felt like afterthoughts and, other times, like distractions from the larger themes of the book. They didn’t seem to serve that main narrative arc, and I found myself wishing they’d been handled with a lighter touch.

And Yet…

As someone who is from Pakistan, who speaks English and Urdu and a little bit of French, who writes up subtitles for Bollywood movies on a freelance basis and who dreams of literary greatness, Anisa provides an interesting perspective when it comes to a number of questions:

Who has the right to adopt the markers of a culture? When does such appropriation / appreciation become a sort of cannibalization?

What level of assimilation is required to attain a certain level of respect in specific professional circles, and is this level of assimilation worth it?

What responsibility does a translator have to the original author (or, by extension, what responsibility does any writer have to the person whose story they’re telling)? What do we owe to those whose native languages or stories we twist and transform to suit our own professional purposes?

The ways in which Siddiqi interrogates these topics are so fascinating.

My final thoughts? For this reader, this was not a perfect book. But it was nevertheless a fun and thought-provoking read, and one I’ve already recommended to several people in my life.

Colonialism constructed as cannibalism is at the heart of this disturbing, fast-paced and intriguing novel. All are imbricated – readers/learners, former colonized and colonizers. Circles within circles. The story begins slowly yet always there is an ominous overtone which increases as the story progresses. Theories are undercut by realities and individuals locked into the very systems they critique. Perhaps the sudden end with the future foreclosed or at best uncertain is, therefore, to be expected.