Solarpunk 101

Solarpunk is a subgenre of science fiction that imagines the kind of world we might live in if we all were free enough to create it. Focusing on climate solutions, cooperation, and acceptance, this kind of imaginative work becomes increasingly important as surviving on a warming planet requires more and more sweeping changes and creative strategies.

This summer, in places that never experienced the ramifications of wildfires first hand, many of us walked out of our homes one morning to find an oddly yellowed landscape. It was an otherworldly feeling. I live in New York City, where we can feel especially separate from our environment, and this was perhaps a jolting reminder that climate change is happening to all of us and its effects will change all of our lives in large and small ways. Walking in our temporarily sepia-toned reality reminded me of the cyberpunk worlds I grew up reading about and seeing in movies: dark and with a sense of foreboding and doom.

Solarpunk, as its name might imply, depicts the opposite kind of world. While the characters and species within might have endured cataclysmic change in many of these narratives, society has banded together cooperatively and is living in a somehow better, more moral and just universe in its wake.

First named in 2008, solarpunk is a relatively new genre that is still in the process of being defined. It is hard to track down definitive lists or a united theory of it, although Winston Pei has done quite a comprehensive job tracking the use of the term.

The Monk and Robot Series by Becky Chambers

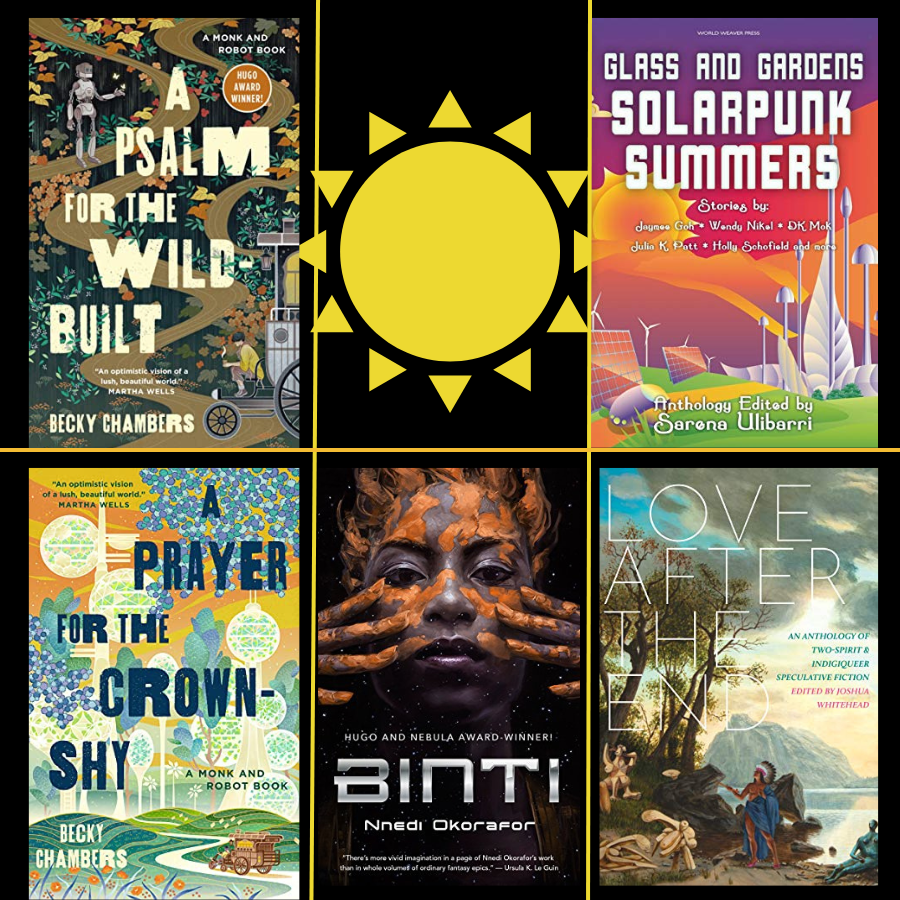

I discovered the genre when I read A Psalm for the Wild-Built followed by its sequel A Prayer for the Crown-Shy in basically two single sittings over the course of a weekend. Tor Books commissioned Becky Chambers to write these two solarpunk novellas, together called the Monk and Robot series, based on the lightness of her popular space opera The Long Way to A Small Angry Planet. This ease permeates Monk and Robot. The series is a quintessential comfort read–offering a calm and cozy world to step into for a while.

The world is Panga, a moon where the robots previously relegated to lives as workers all gave up their work and walked together into the forest. And, amazingly, humanity elected to let them go. Panga has changed its ways, electing to undergo a process of degrowth while uncoupling from technology. This is part of the vow they’ve made to never subjugate others for their comfort again.

In this much changed society, Sibling Dex, a garden monk, has grown bored with their occupation and decides to pursue a new one: tea monk. They must learn to brew the perfect blend of herbs to aid any number of ailments and, most importantly, to listen to those who are ailing. But even after becoming very accomplished in their new vocation, Dex is in search of still more meaning and wanders into the wild, where they unwittingly happen upon the first encounter between robots and humans since their separation. Splendid Speckled Mosscap has been sent by the robots to go out and find what it is that humans need. With kindness and mutual respect through difference, Dex and Splendid Speckled Mosscap explore the many ways to answer that question.

There are scare moments of tension and conflict but even those are minor. Everyone always does the right thing. And the books themselves are a balm–the kind of comfort a tea monk might prescribe.

A Literature of Optimism

I think this kind of utopian thinking is important for more than just our comfort, but there is something satisfying about the combination of the two. Imagining creative responses to climate change and just societies based on reciprocity and mutual aid might help us to find our way there. There is so much work to be done. And, at the same time, sometimes the reality in which we find ourselves requires us to take a break. Solarpunk fulfills these warring needs.

Owing to the newness (and niche nature) of the genre, seeking solarpunk novels to read after Monk and Robot, I have read books that I saw suggested as examples only to finish them wondering if they are solarpunk at all. One example of this is the Murderbot series by Martha Wells. Ultimately it does share a general kind of lightness, a character driven narrative, and a relatable, lovable and often anxious robot main character with Monk and Robot. And, while the Universe the story is set in is not all kittens and rainbows, there is a thread of kindness and ethical treatment throughout the series, and we eventually land on the Preservation Alliance, a diverse society with free food, shelter, education, and medical care.

The core uniting factor of solarpunk is its optimism. Solarpunk worlds–or universes as the case may be–are often community based, post-capitalist, and ecologically centered. Like the genre itself, communities’ borders might be less solid than the ones we are used to. Gender and sexuality are expansive and individualized. People and life forms of all kinds are accepted and many of them live in some degree of harmony.

This shines through the whole series of genre-defining collections, organized around optimism, science, and hope edited by Sarena Ulibarri: Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers; Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Winters; and Multispecies Cities: Solarpunk Urban Futures.

Centering Indigenous, African, and Queer Voices

Those whose identities and communities have been historically oppressed are often centered in solarpunk, as are societies who have a close relationship to nature. Solarpunk novels can lift Indigenous voices and indicate where long held practices and beliefs–from communal living to tested methods for stewarding the natural world–provide strategies and inspiration for better futures. There is also overlap in with Afro- and AfricanFuturism. It makes sense that the literature that considers the most hopeful outcomes of climate change would value these worldviews, cultural practices and knowledge.

In Binti by Nnedi Okorafor, Binti is a Himba girl, a member of the real Indigenous group that inhabits Northern Namibia in Southern Africa. She is the first of her people to be accepted to intergalactic Oomza Uni and she must leave everything she knows behind in order to go. She feels like a stranger among the other species, but it is the qualities that set her apart that make her uniquely well-positioned to navigate the conflicts she encounters.

These are themes in some but not all of the stories in Love after the End: An Anthology of Two-Spirit and Indigiqueer Speculative Fiction, a collection of Indigenous futures by two spirit and queer Indigenous writers from across Turtle Island. The stories show collective and postcolonial responses to the end of the world as we know it and show how we might plant and water the seeds for the next one.

World-making

Lists of solarpunk literature sometimes include Woman on the Edge of Time by Margie Piercy, The Dispossessed or Always Coming Home by Ursula K. Le Guin. I like to think of those as solarpunk’s forebears, for their utopianism, their anarchism, their progressive views of sexuality and society. They offered radical views of the future.

Like those seminal novels, solarpunk is progressive and principled. It is post-colonial, and post-capitalist. These stories, like most science fiction, are about world-building. But solarpunk doesn’t just offer a world, it offers a worldview. It doesn’t give us a roadmap to a better, kinder, more inclusive and sustainable planet. But it reminds us that one is possible.

Woow loved this thank you!

Pingback: The KWL Quill – January 2025 Kobo Writing Life