The deal was: She’d pay me $200, I’d shave my head, and I’d buy the amp. Hair grows back. Vox AC15s are forever.

When I was 16 years old, I was the lead guitarist of a rock band and my weapon of choice was not my axe (rock star talk for a guitar) but, instead, my hair. A medium-sized afro lacking moisture, curl definition, and shape. I loved it. I looked just like the Rock Band avatar I made when I was 7. But, indeed, it was damaged and a refresher was needed. The best way to do that was to follow in the steps of my mother, grandmother, great-grandmother, and many of my other ancestors and partake in the “Big Chop.”

For those unfamiliar, the “big chop” usually refers to the act of cutting off (or shaving off) all of one’s hair in order to start (or in my case “restart”) one’s natural hair journey. This is a practice most common with Black women or women of African descent.

I had never walked the path of the big chop. I had simply watched my mother go through her journey. I marveled at my grandmother’s (Nana) famous and semi-permanent shortcut and all the ways she styled it despite hardly having an inch of hair on her head. (Don’t tell her I said that.) And apparently, my great-grandmother had one of the most impressive big chops of all time. It was always discussed as an urban legend, which is understandable. For as long as I had known her, my great-grandmother (whom I called Grandma) wore two long braids. One on each side of her head, proudly highlighting both her Black and Black Foot heritage.

My mother’s big chop was gorgeous and done several years before natural hair had returned as an acceptable way for a Black woman to wear her hair. She received several backhanded compliments and passive-aggressive comments about how she looked much better with relaxed hair. But to me, she was regal. The very definition of beauty. And yet I hated the idea of going through the journey myself.

My hair was my power. It’s what made me “cool.” It was the representation I wanted so desperately for myself. A Black woman absolutely shredding on guitar with a big-ass natural. I wanted that image to live and breathe inside of me and every other Black femme to follow after me. And as the Black girl who played “white people music” on guitar (despite the fact that Black people are without a doubt the heart and soul of R&B, the blues, and rock and roll, if nothing else [but also everything else, yes, including country]), my afro was what made me Black. Or that’s how I felt.

But none of that was spoken. Instead, a deal was made where I ended up with $200, and somewhere down the line, this would somehow turn into an “I told you so, MOM!” Five years later, here I am. Bald and blacker than ever. And to celebrate my five-year anniversary here are five things I’ve learned with no hair:

1. Body Temperature

It was immediate. I hadn’t realized how much my afro had protected me and kept me warm. As soon as the last strand of hair hit the floor, I felt an internal breeziness I had never felt before. It was my dad, a man who has been bald for my entire life, who taught me how to survive the Midwest and East Coast with no hair. I learned to harness the power of the breeze against my head. We bought hats in many different styles and colors. I even crocheted some. Hoodie hoods became more crucial than central air systems. I learned that the perfect balance between a hoodie/hat & sock/slipper combo can last you throughout the year. I have, in years, absolutely mastered body temperature regulation and it is easily one of my greatest feats.

2. Chopping My Own Big Chop

In college, pre-pandemic, twice a month, I would go to the Afro-Latinx barbershop to get my haircut. I never knew the name of the man who cut my hair. He hardly spoke to me and, when he did, only in Spanish. But he was mean with those clippers. He was the only barber I ever went to who didn’t cut my hair in an attempt to set me up for my career as a SoundCloud rapper. Long story short, COVID happened and I found myself in Trump Country, Florida, in desperate need of a haircut during the George Floyd riots. It was at this time that I ordered a pair of clippers and learned how to cut my own hair.

3. Working Out

You have not lived until you’ve swum with nothing but a wish strapped to the top of your head. I was once told, and this is real, that I was “aerodynamic” as a swimmer. Now, having shaved my head, I gotta say I feel like it. Swim caps actually fit on my head now! Exercising is amazing with no hair. Running? The breeze dancing along the top of your scalp? I live for it. This became increasingly exciting as I began my journey with yoga performing headstands and plow pose without worrying if my afro had morphed itself into a straight line.

4. Rain (& Travel)

I’ve learned not to fear the rain. Mostly because I don’t have to. All my curly-haired people know what I mean. Humidity is not a friend. But by having short hair, I can finally do what white women in the middle of romantic comedies do without having to put a grocery bag on my head! In fact, traveling as a whole is a lot more exciting. No more coconut oil stains on airplane and train seats. At least, not as big as they used to be. Travel-sized containers actually fit enough product to last me the whole trip. And with no hair, I can get up at a normal time instead of fighting jet lag and getting up several hours earlier than everyone else to de-twist my hair, pick it out, and shape it just so it can get body-slammed by an unfamiliar climate setting. If you know, you know.

5. To Be Young, Black, & Nearly Bald

I shaved my head for the first time when I was 16, three months before my 17th birthday, which means that immediately after I shaved my head, I had to go home so I could prepare for another day of high school. The thought of this alone was almost not worth the AC15. I hated high school. I hated being perceived and high school was a place where one was regularly perceived. But instead of laughter, I got whispers and stares which, in so many ways, could be worse. But the day went quietly. At least for the most part. Quiet was good. Great. But one girl tapped me on the shoulder, leaned over, and said, “You look really pretty,” before immediately swiveling back around in her seat and continuing her work. This was somewhat of a mixed single but, years later, my partner, whom I met in high school, would tell me it was the first time he ever really saw me. This was two and a half years into our friendship.

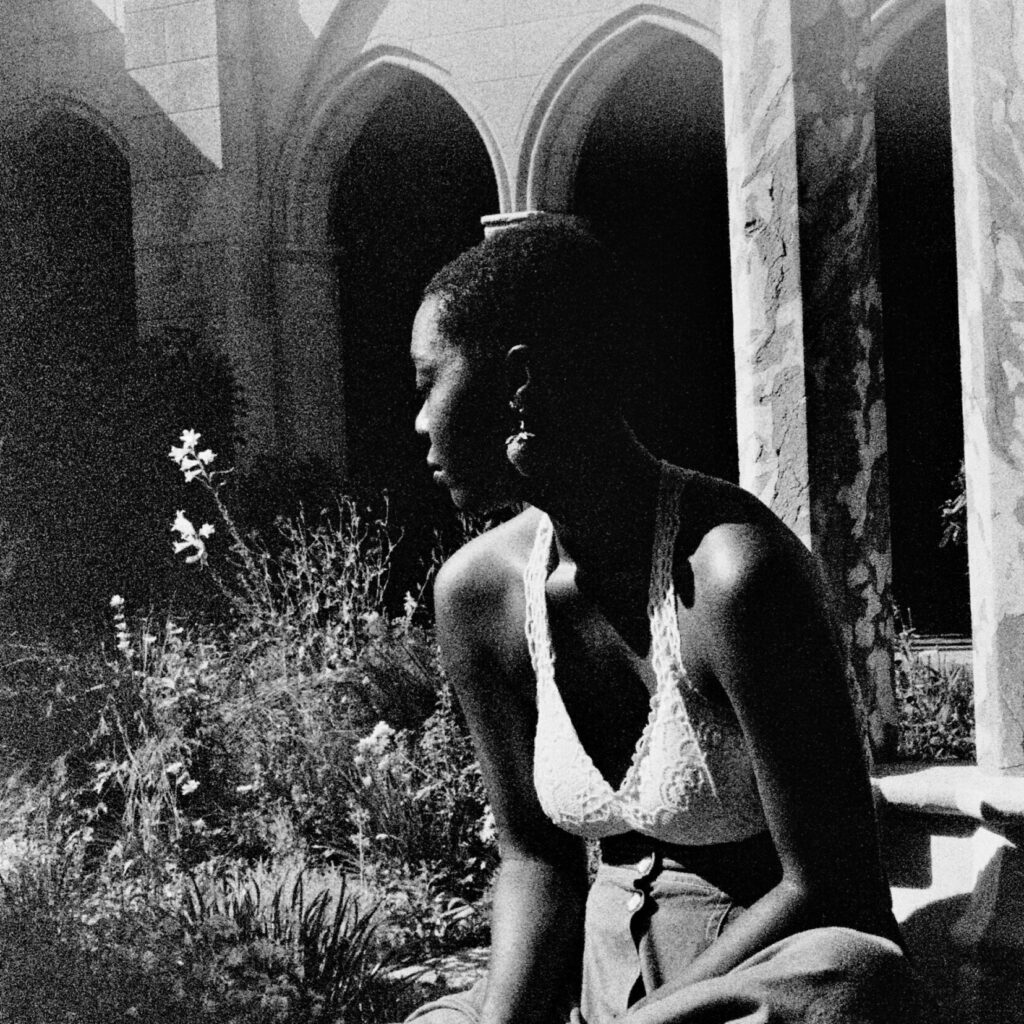

Looking back on the photos of me on stage with my very dry and stiff afro, I don’t see myself. It’s in the time-lapse video of me getting my hair cut for the first time that I see Alana climb out from under her hair and say hello for the time. This is not something that came immediately. It was something I realized with time. Feeling like myself in the mirror took just as much time as it took to feel like myself inside, but shaving my head helped me learn what didn’t fit. At least for me.

In finding myself externally, I looked to my mother, who I closely resemble. A woman who looks just like her mother, who looks just like her mother, and it was during this time that I realized we all inherited my great-grandmother’s rather large and long head. But in that, I saw in front of me my blood, history, and ancestry. A community and representation.

During the George Floyd riots, my “Black card” became something much more than a place to rest my afro pick. Instead, it became protesting, soul food, Angela Davis, Black-owned businesses, cocoa butter, and reading where I found myself in books, like Passing by Nella Larsen, Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid, and The Final Revival of Opal & Nev by Dawnie Walton, which eventually led me to places and people like Cafe Con Libros, Trae of blkbookswap, and Fayola of the Reading 4 Black Lives Project, all of whom rock and celebrate what it means to be Black right now and also have short cropped naturals of various colors.

In college, I studied jazz through the lens of gender and discovered people like Mary Lou Williams, Dorothy Ashby, Esperanza Spalding, Hazel Scott, Sister Rosetta Sharpe, Alice Coltrane, Billie Holiday, and Brittany Howard as well as many of my peers who were breaking from the gender roles set for femme Black women while reconstructing music as a whole.

When I moved to Brooklyn, I discovered there were a plethora of Black women just like me doing yoga, practicing pescetarianism, code-switching, reading in the park, dressing in cottage core, and listening to and thoroughly enjoying bands like The Beatles. All things I was told throughout my whole life were “white,” often followed up with some comment heavily implying that I was some tree-hugging “Oreo” when in reality I was just Black, gay, and in the business of IBS.

But it wasn’t until I started Bipop, a non-profit that provides music instruction to women of color and the non-binary community, that it all sort’ve hit me. As students started signing up and our social media started picking up, many of the DMs we were getting, both as an organization and on my personal accounts, were in celebration of seeing a Black woman with a short cropped natural playing stuff like Heart and Beck on guitar and drums or whatever else I was messing around with at the time. And this didn’t spark joy because of all the praise that was coming my way, but it sparked joy because I had become, with no hair at all, what I thought I could only be with the afro. I wouldn’t call my lack of hair a superpower, per se, but it is an extension of me. I’ve since begun to own the fact that I am cool. I am the representation I wanted to see at 7. I’m the representation I want to see now!

And though there aren’t as many as I would like to see, there are plenty of women and non-binary people (of color) shredding guitar all over the place. So happy fifth big chop anniversary to me. I wonder what I’ll learn next.