This post may include affiliate links, which means we make a small commission on any sales. This commission helps Feminist Book Club pay our contributors, so thanks for supporting small, independent media!

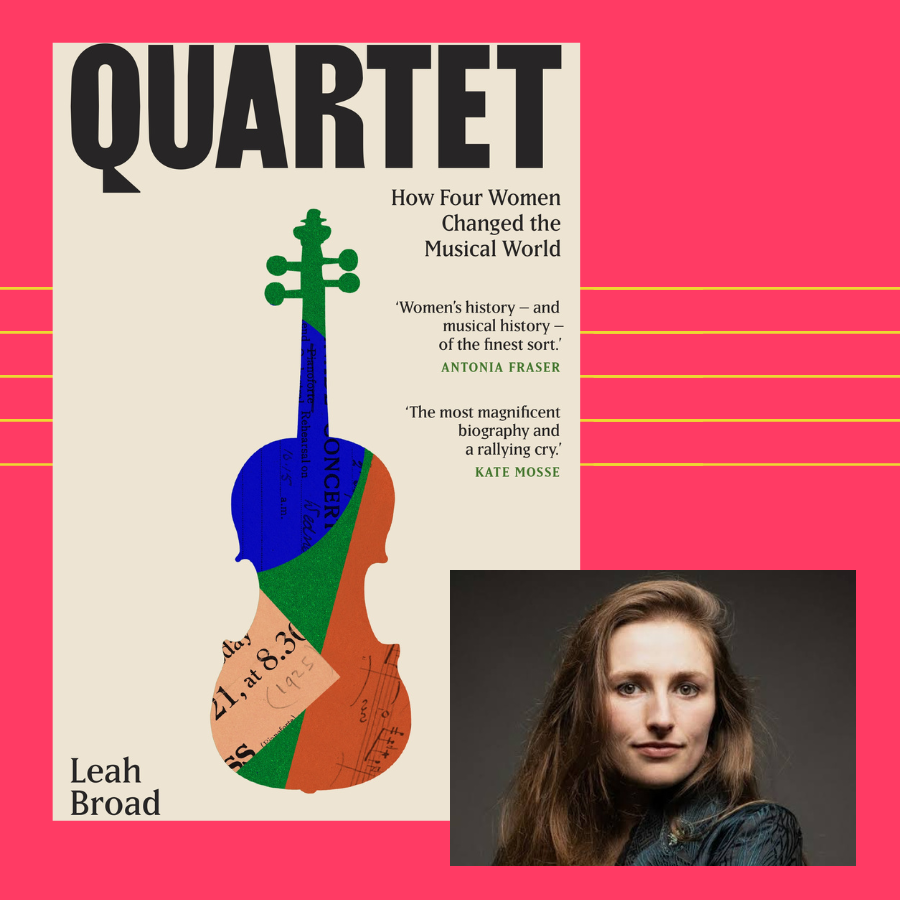

As Feminist Book Club’s resident historical female composers stan, it’s my duty to let readers know about this incredible new book from Dr. Leah Broad. Leah is a historian at the University of Oxford who focuses on women in music in the twentieth century. Quartet is her group biography about British composers Ethel Smyth, Doreen Carwithen, Rebecca Clarke and Dorothy Howell—all musicians who were celebrities during their time. Written as a beautiful tapestry of these four composers’ complex lives, Quartet is a fascinating and insightful dive into the intersection of women’s history and music history in turn-of-the-century England. I spoke with Leah about how this project came together and why an accurate understanding of the past is important to a more equitable future.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Why did you decide to write a group biography of four composers instead of focusing on just one of them?

Any one of them could have been a subject on their own, but there is a real tendency to isolate women and to present them as the “first” and the “only,” and that’s really damaging. Yes, it’s important to acknowledge breakthroughs when they happen, but women have always been composing classical music. It’s not like there were only four women composing so I wrote about them; I had to choose who to leave out. I wanted to show how networks are built, that there was a community of composers working at this time, and that there was no one way of being a composer or a woman in this period. These women deal with the various obstacles that they all face in really different ways, and for me it was important to show that there are so many different ways of being a musical human.

Who are the women of Quartet and why are each of them important?

Ethel Smyth is the first woman. She’s famous as the composer of six operas. She was a suffragette, she wrote the anthem for the women’s suffrage movement, and she was the lover of pretty much anyone who was anyone interesting in the early 20th century—like Virginia Woolf, Emmeline Pankhurst, Edith Somerville—her address book is crazy! And her music’s fantastic. She really confronts gender problems in the industry. I think it’s impossible—or it should be impossible—to write a history of British music without Ethel Smyth. It’s been done before, but I think that’s very wrong.

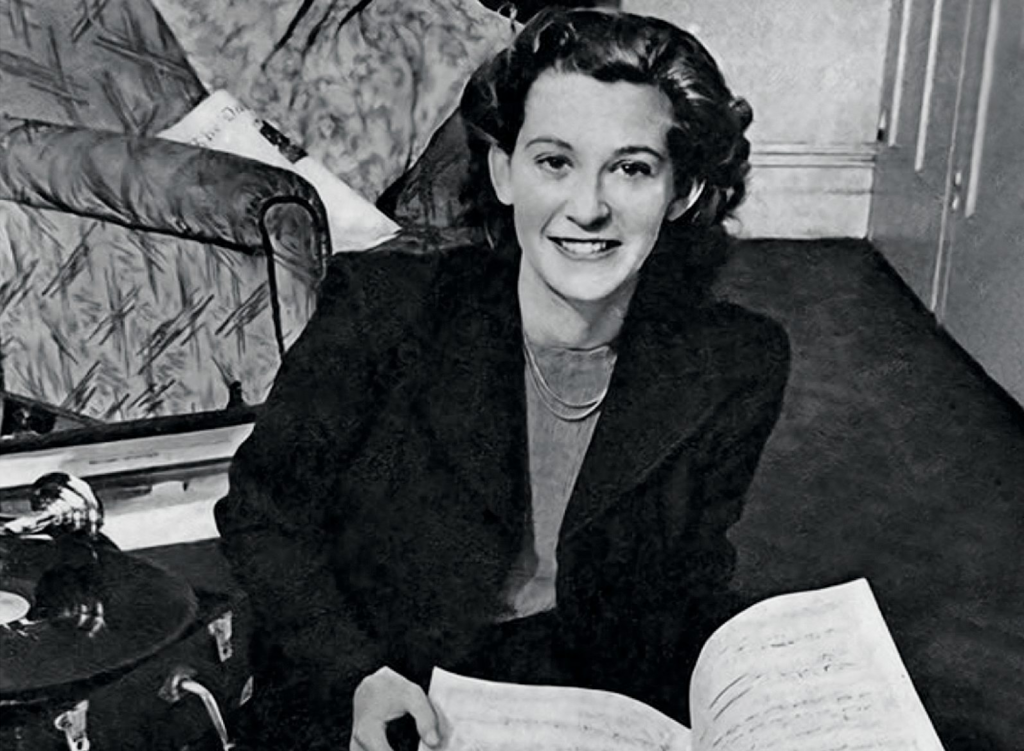

Rebecca Clarke is a performer-composer. She’s famous as both a composer and a viola player. This was really unusual at the time, because the viola was not usually thought of as a solo instrument; she was one of the people who changed that. She writes beautifully for the instrument and she was also one of the first women in the UK to be employed in a professional orchestra. Before 1913, professional orchestras were closed to women, and we’re still dealing with that legacy.

Dorothy Howell shot to fame in 1919 at the Proms where an orchestral work of hers was done and she became an overnight sensation. She wrote a lot of religious music. She was Catholic and her faith was very important to her. She wrote incredible orchestral music.

And then Doreen Carwithen is a film composer, primarily. She scored over 30 films, and that’s still something that seems a bit unusual for women to do today—film composition. That’s why I really wanted her in the book as well.

The book begins not in a concert hall, but outside at a Women’s Social and Political Union event in 1930. The photo of Ethel Smyth conducting the Metropolitan Police Band is so powerful. When did you know that you would start the book with this scene?

I wrote the Prelude last because it ties everything together. That’s when it was like, “Okay, so having put together this book, what do I want people to think about as they’re reading this?” It just became so obvious how political these women’s lives were. Whether they wanted it or not, they become political. And this isn’t just a book about music. It’s a social history, and we can’t really look at women working in classical music without also looking at the history of women’s rights. These things are just so intertwined.

This scene shows Ethel Smyth supporting another woman (she’s conducting Dorothy Howell’s music), and also supporting this woman who was probably her lover (Emmeline Pankhurst). By this point, Ethel Smyth is an establishment figure. She’s got three doctorates, she’s got a damehood, she is very famous in British life. And she’s also a political figure. These people’s lives didn’t happen shut off in a concert hall. They were in papers, they were really working with the music of their day. Ethel Smyth’s “The March of the Women” was sung everywhere. Her music was popular. Starting with this scene was a way of saying: “Okay, from page one, you’re reading a feminist book I’m afraid!”

You write about the idea that music was considered “beyond women’s reach” at this time. As a woman in music yourself, did you feel any rage when researching for this book?

Yes. I think anger is a really important part of this type of scholarship. I did get cross writing this book because it got to the point where I was trying to find ways to not repeat myself—because I talk about the performances and I talk about how the music was received, and it got to the point where I was sort of writing, “and then there was a performance and the reviews were really sexist and the music disappeared.” And there’s only so many times you can say that in a 400-page book before it starts to get really boring.

I did feel a lot of frustration writing this. I’m trying to channel that into a constructive energy of going, “Okay, I’ve analyzed a load of structural barriers which is why this stuff hasn’t changed. What do we need to do to change?” I think we are seeing change now, and what I really would love to see is this change become permanent. Something that happens a lot in the book and is perhaps the most frustrating thing, is these cycles of interest in women’s music: you have a peak where suddenly they’re in fashion, and then women aren’t in fashion anymore and they vanish again. That’s so frustrating. We have to find ways to keep momentum going and to actually create lasting change—to get this music published, to get it performed, to get it recorded—so people can make up their minds for themselves.

So long as women are the “first” or the “only,” they can’t be the favorite. They are isolated. How can you possibly make somebody your favorite composer if you’ve never heard anything that they’ve written? So I’m trying to constructively say, “Okay, what can we do to create lasting change?” I see this book as one tiny drop in the ocean of a big network of collaboration that will hopefully bring about the change that we need.

You write: “Historical forgetting is such a powerful form of erasure.” Your book is one way of combatting this erasure. If we work to bring stories like these composers’ lives to light, what effect do you think this can have on the future of classical music?

I really hope it stops us expending energy on having to do the same breakthroughs over and over again. Like, Ethel Smyth was held up as the first woman to write an opera—oh my god, that had been done three centuries before! Come on, guys! I think that is really important. It provides role models, it provides a network for people, and it provides a history of, “Okay, you don’t have to be alone, there are ways of doing this.” It can be really lonely always feeling like you’re the pioneer.

It still stuns me how little music by women is performed. I hope that anything that helps people connect with these historical composers will help to change that. I would love to get to the point where a composer’s gender is completely unremarkable. But until we’ve got to the point where people aren’t like, “Oh, we’ve got a woman on the podium?!”—you know, all the reception around Tár for example, the huge conversation that film has generated—we’ve got a really long way to go. Women are still seen as exceptional.

For readers who have never heard these composers’ music before, what would you recommend they start with?

For Ethel Smyth, I’d go with her song “Possession.” She’s famous for her really big stuff, but this song was dedicated to Emmeline Pankhurst, and it was written when Ethel Smyth was basically watching Emmeline Pankhurst waste away from her hunger strikes in prison. It’s a song about letting go of somebody who you love because you know you can’t control them and hold onto them. It’s so poignant, and it just encapsulates their relationship at that particular point so well and it’s a beautiful piece of music. It shows a really intimate side of Ethel Smyth that I love.

Rebecca Clarke—it’s got to be the Viola Sonata. Like, the first movement just makes you go, “Wow! Who the hell is this? I am listening to you; you have something to say!”

Dorothy Howell—so little of Dorothy Howell’s music has been recorded yet, but I have to recommend Lamia, which is the piece that launched her to fame.

Doreen Carwithen… there’s so much! I have such a soft spot for her Piano Concerto. But if you like Vaughan Williams and you’re into that style, then try her Suffolk Suite, which is really good fun. Though all her music is amazing.

Why should readers who are not into classical music care about this history?

The book is completely written for people who don’t know anything about classical music. I think they should care about this history because it’s women’s history. If we lock women composers out of our history, that’s sort of going, “Okay, that’s a whole swathe of our existence that doesn’t matter.”

These composers are part of a group of creative women who are trying to forge creative identities and professional identities at the turn of the century. It’s no coincidence, for example, that Ethel Smyth was best friends with Virginia Woolf. They’re not separate. They’re all part of this network of women building their own identities.

For the most accurate, up-to-date information about Rebecca Clarke’s life, career, and music, see her official website, rebeccaclarkecomposer.com. All of Clarke’s music either has been published or is in production, with releases planned during 2023. The website offers a complete works-list, a detailed discography, and many exemplary performances on video.