This post may include affiliate links, which means we make a small commission on any sales. This commission helps Feminist Book Club pay our contributors, so thanks for supporting small, independent media!

About the Book

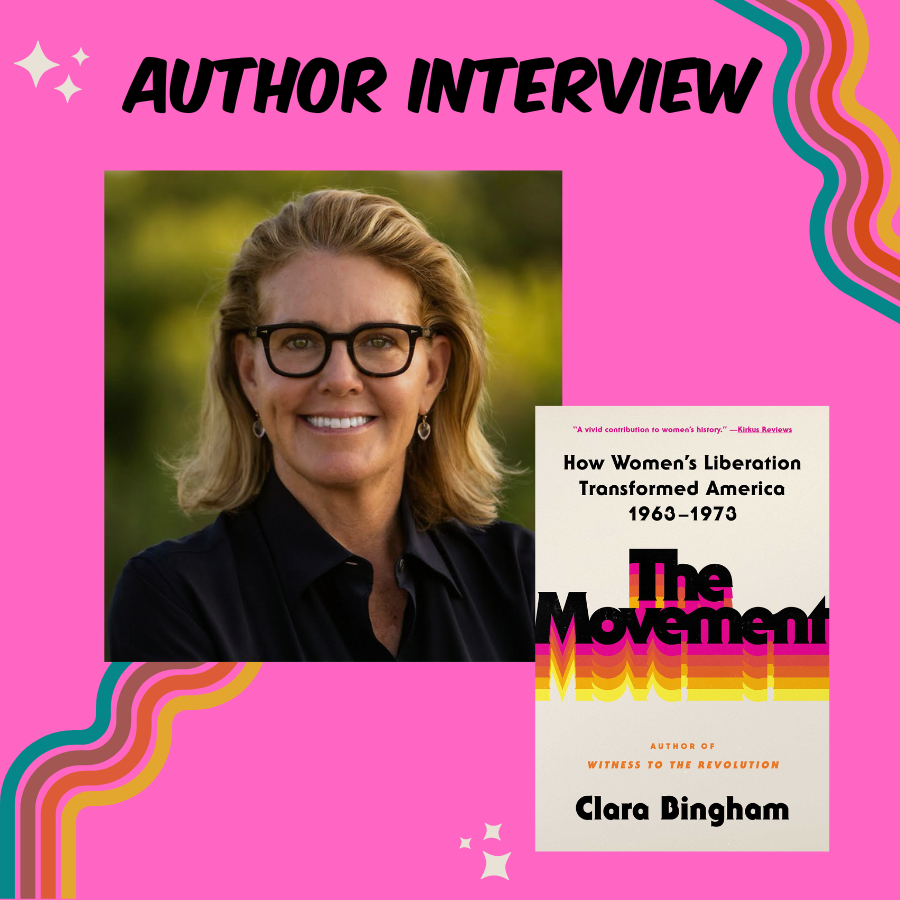

The Movement: How Women’s Liberation Transformed America, 1963-1973 by Clara Bingham is an oral history that encapsulates second wave feminism and the contributions of feminists during a major revolutionary shift in public consciousness. The author spent five years researching and writing this project. Working on it enabled her to meet many women (and a few men) who had invaluable knowledge to share.

The book is a chronological walk-through of second-wave feminism. Each chapter provides historical context within the movement, and then follows the core: women’s experiences during that time period in their own words.

We hear stories from private homes, college campuses, the workplace, the backgrounds of planned strikes and marches, from podiums and newsrooms. The author features women and leaders from all kinds of backgrounds, including Shirley Chisholm, Barbara Smith, Florynce Kennedy, Aileen Hernandez, Frances Beal, and Muriel Fox. The format makes the book feel as if the narrators are in conversation with each other, and with the reader. This kind of connection made possible on the page speaks to the lasting impact of the oral tradition of storytelling and its place in creating community.

In a country with more and more reproductive rights, legal protections, and bodily autonomy either erased and/or under threat, and with the current political climate entrenched with casual misogyny, it can be hard to find answers to our pressing problems. It is more important than ever to read stories by and about women, because as history has shown us, the solutions we need can almost always be found there.

Clara was so gracious about taking my (many!) questions over email, and shared some great insight about the past, present, and future—plus some great book recommendations!

Interview with the Author

Starting off with a big question right off the bat, but it’s a favorite to ask around these parts: What does feminism mean to you?

To me, feminism means, very simply, the belief that men and women should have equal respect and equal rights under the law.

You wrote that you started your interviews about The Movement at civil rights and radical feminist activist and journalist Susan Brownmiller’s home in 2019. How did you go from there? What was the biggest challenge of finding who to interview?

Geography played a big role in who I interviewed at the beginning of my journey, before COVID shut down the world. Like Susan Brownmiller, I live in New York City, and at first, I interviewed women who also lived in New York like Marilyn Webb, Emily Goodman, Margo Jefferson, Nancy Stearns, and Barbara Winslow. I also traveled to Boston, where I interviewed some of the founders of Our Bodies Ourselves, Joan Ditzion, Miriam Hawley, Jane Pincus, and Norma Swenson. Also in Boston, I tracked down Jane O’Reilly, who wrote the cover story in the first issue of Ms. Magazine, “The Housewife’s Moment of Truth.” After COVID, I moved my interviews to Zoom, which was more efficient, but not nearly as much fun. But it made it easier to get to more people who lived in other parts of the country.

The biggest challenge was convincing people to trust me and talk to me, so after each interview, I asked the subject for a list of people I should talk to next, and a personal introduction.

Your previous book, Witness to the Revolution, is an oral history that focuses on the Vietnam antiwar movement of the late sixties. You’ve spent a lot of time writing oral histories. In your experience, what is the most challenging aspect of compiling an oral history? The most rewarding?

The most challenging is asking people to remember details about their lives that happened over 50 years ago! When memories were (understandably) vague, I would try to supplement archival material—old interviews they may have done decades earlier. (Smith’s and Harvard’s libraries had a very helpful bank of oral history interviews with second-wave feminists that I relied on; so did the Library of Congress and other archives.)

The most rewarding part of writing an oral history narrative is when I can find several good sources/people who were at the same place at the same time but had different perspectives and experiences—that’s when a chapter can fly. Oral histories can be lively, not dense. They are like reading dialogue, and they can also be more personal and emotional. Since this movement was such a personal one (“the personal is political”) I felt that telling its history through first-person voice was the best way to convey, with emotion and authenticity, what it felt like to be on the front lines of change.

The accounts included in the book are deeply moving, and most of them very heavy. I imagine it took an emotional and mental toll while working. How did you balance your work with taking care of yourself during the writing of the book?

The abortion sections were of course the hardest to hear in interviews and the hardest to write in the book…and then on June 24, 2022, when the news came down that the Supreme Court had reversed Roe v. Wade, I was actually writing one of the tough abortion chapters and my heart just sank. Suddenly, the past roared into the present, and the lives of women who are now in their 80s will, for the first time in 50 years, be similar to the lives of women who live in abortion-ban states. It was devastating. But so many of the women I interviewed had such inspiring and heroic stories that I found myself being more energized and inspired than depressed during most of the writing process.

You mentioned that you were born the year this book begins. What was it like revisiting the decade in which you grew up, this time from an experienced adult’s perspective?

I was born in 1963, and grew up in New York City on the upper west side, and I have strong memories of idolizing Shirley Chisholm and Bella Abzug as a young girl. They both were members of Congress from New York, and I taped their campaign posters to my bedroom wall. My mother was a freelance photographer, and she took photos for the Village Voice newspaper and followed Chisholm on the campaign trail in 1972. So, revisiting this time of tumult, change, and excitement as an adult helped me connect a lot of dots from my childhood and it also helped me understand my mother and her generation so much better.

How does The Movement tie into the general history of how women’s stories get recorded?

Women’s stories are often overlooked and distorted, and The Movement is an attempt to put women’s voices and stories front and center.

You touched on the fact that for at least a generation, historians have traditionally ignored the vital role of women of color in the movement, and were slow to include the contributions of BIPOC and LGBTQ+ feminists. In The Movement, you attempted to “partially correct the record” by highlighting WoC voices, particularly those of Black women leaders. How does this speak to the larger issue of how history is mainly told from men’s perspective?

When I read the contemporary mainstream press accounts of the women’s movement, I was shocked by how unapologetically sexist the (white male) newspaper, magazine, and television reporters were at the time. They ridiculed the early feminists and belittled their cause. In the case of LGBTQ+ women (and men too) the press was downright vicious. When it came to the contributions of women of color, the mainstream press almost completely ignored their contributions. In the past twenty years or so, women have started to take back our history and correct—or fill in—the record. The Movement is just part of a new group of books that have attempted to tell the story of the second wave feminist movement more accurately and equitably.

As feminist readers, how can we engage with history that has traditionally favored white, male voices? How can we prioritize intersectionality?

Look for histories written by women about women. There are lots of them out there!

Given the current social and political climate, and the parallels between present day and the decade The Movement covers (1963-1973), where can we go from here? Where should we look to for hope?

I think there is a lot of hope, and maybe that’s because I’m writing this the morning after the Harris-Trump presidential debate. We have a woman of color running for president who is smarter, more qualified, and more of a leader than her white, male, aging opponent. How good is that??

Of course, restoring reproductive rights is going to be a long, hard, fight and there is still so much to do, but I feel confident that enough Americans understand that without reproductive rights, women cannot have equal rights, and I hope that with enough organizing, a majority of Americans will go to the polls in November and elect a historically important candidate who can lead this country with dignity and respect.

I’ll close off with another favorite question we love to ask: What are you reading at the moment?

I just finished Percival Everett’s James, and found it incredibly brilliant and powerful. Before James, I read The Friday Afternoon Club, a memoir by Griffin Dunne, which I loved for its intimacy and frankness. Next on my list is Rachel Kushner’s new novel Creation Lake. I can’t wait.

Thank you so much to Clara Bingham for discussing her book with us. You can learn more about her and her work on her website. If you’re interested in more history from Clara, you should check out her 2017 book Witness to the Revolution.