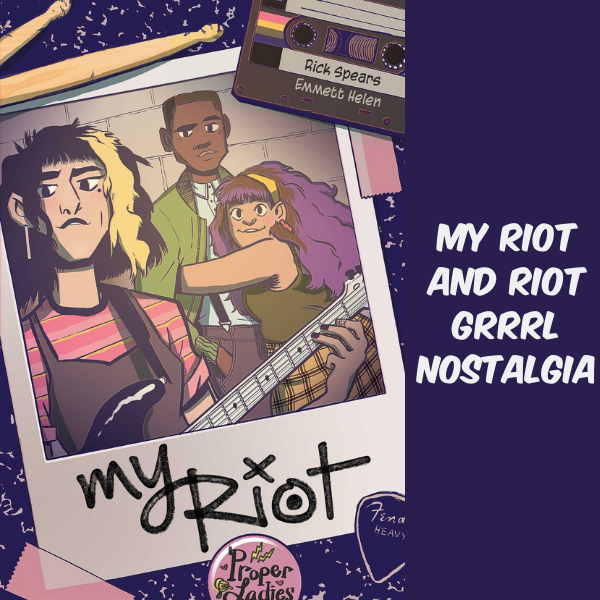

When My Riot — written by Rick Spears and with art by Emmett Helen — opens, it’s 1991 and the 17-year-old Valerie Simmons is chugging along through an average suburban life, landing her first job at an ice cream shop and training to be a ballerina.

But then, a rookie police officer murders a Salvadorian man, sparking two days of rioting by Black and Latino youth in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood of Washington, D.C., and Valerie begins to question the safe little bubble she’s lived in her entire life.

At about the same time, she meets Kat, the young woman who will become her best friend, and she attends her very first punk show. The violent energy and the danger of the mosh pit remind her of the riots — and she realizes she wants more. “For a moment,” says our narrator, “we weren’t whatever we were in the real world. In the pit, we were just motion.”

Valerie and Kat start their own band — The Proper Ladies — soon bringing on their friend Rudie, a SHARP (Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice), on bass.

The rest of the graphic novel takes readers through a fictionalized accounting of what most groups must have experienced during the Riot Grrrl movement. There is the immediate connection with a network of girls who seem hungry for what the Proper Ladies are singing. There is the reference to “Girls to the front,” a phrase popularized by Kathleen Hanna of Bikini Kill that was quite literally a demand for guys at gigs to take a step back and let girls come forward so they could enjoy musical acts without fear of attack or mosh pit violence. There are lyrics about the bullshit nature of beauty norms and about unabashed sexuality. There is the word “SLUT” written in bright red lipstick on bare, outstretched arms. There is the growing network of zines. There is life lived on the road.

The Riot Grrrl Movement

I was only a preteen when the Riot Grrrl movement began to emerge in the early ’90s. While female musicians were storming the stage to sing about the patriarchy, sexual violence, domestic abuse, and female empowerment, I was pulling posters out of BOP magazine and listening to Meat Loaf. Bryan Adams. Boyz II Men. (Shut up.)

Still, as I stewed in my own obliviousness, bands like Bikini Kill, Heavens to Betsy, and Linus were changing people’s views of who got to be on stage and, more importantly, what women were allowed to say out loud. With yowling vocals and outspoken lyrics, they forced people to sit up and take notice.

Still, as I stewed in my own obliviousness, bands like Bikini Kill, Heavens to Betsy, and Linus were changing people’s views of who got to be on stage and, more importantly, what women were allowed to say out loud. With yowling vocals and outspoken lyrics, they forced people to sit up and take notice.

According to ’90s Bitch by Allison Yarrow, not all of these women necessarily felt called to make music. Rather, they felt that their very girlhood was under attack, and they wanted to push back.

“Not only do we live in a totally fucked-up patriarchal society run by white men who don’t represent our interests at all, but we are in a country where those people don’t care if we live or die,” said Bikini Kill drummer Tobi Vail. “And that’s pretty scary.” (Well, that sounds familiar…)

At the time, to be a part of the movement was to “[make] art around our anger,” as Rebecca Odes of Love Child put it. It was protest music… a way to get out a message without waving signs at a protest.

Eventually, the music inspired other forms of DIY protest, including consciousness-raising gatherings and, most notably, the creation of zines, limited-batch, self-published magazines containing everything from poetry to raging manifestas to collage-work. These handmade publications were often sold at shows or sent out to growing mailing lists.

In everything, they were fierce and unapologetic. As Yarrow writes, “Riot Grrrls attempted to celebrate and normalize female anger.”

The Limitations of Riot Grrrl

As galvanizing as Riot Grrrl was, however, it eventually began to show signs of wear and fracture. As middle-class white girls enjoyed their status as the face of a movement, women of color were often pushed to the side, despite their many contributions.

In the fourth issue of GUNK (excerpted here), a zine created by Ramdasha Bikceem, she writes of how white grrrls were free to push back against beauty and style norms thanks to their whiteness.

“White kids in general, regardless if they are punk or not, can get away with having green Mohawks and pierced lips ’cause no matter how much they deviated from the norms of society their whiteness always shows through,” she writes. “For instance, I’ll go out somewhere with my friends who all look equally as weird as me, but say we get hassled by the cops for skating or something. That cop is going to remember my face a lot clearer than say one of my white girlfriends.”

“White kids in general, regardless if they are punk or not, can get away with having green Mohawks and pierced lips ’cause no matter how much they deviated from the norms of society their whiteness always shows through,” she writes. “For instance, I’ll go out somewhere with my friends who all look equally as weird as me, but say we get hassled by the cops for skating or something. That cop is going to remember my face a lot clearer than say one of my white girlfriends.”

In an attempt to create alternatives to the already-existing scene, in addition to creating their own zines, some women of color also created their own spaces to share their music. In the late ’90s, for example, hardcore musician Tamar-kali Brown founded Sista Grrrl Riots, a series of one-night gatherings for and by Black female musicians. It was an alternative to both the male-dominated punk scene and the white-dominated Riot Grrrl scene.

Vietnamese-born American scholar, punk, and zine author Mimi Thi Nguyen makes the same point in a paper on “Riot Grrrl, Race, and Revival,” writing about how “the gender deviance displayed by riot grrrls is a privilege to which only middle-class white girls have access.”

But it seems that white girls just didn’t get it. In her zine Mamasita, Bianca Ortiz writes, “I am sick of being the example, the teacher, the scapegoat, the leader, the half Mexican girl in the group of ‘allies’ who either attempt to praise me or destroy me, or both at once.”

It’s a problem people of color still grapple with today. Or rather, white people grapple with it… and people of color are forced to deal with it.

The End of a Movement

Beyond the schisms within, Yarrow writes that the movement fizzled out by 1997 thanks to the commodification and commercialism of both its aesthetic and its message.

Messages of aggression and rage became watered down, leading to groups like the Spice Girls, who sang about “girl power,” and angry rockers like Fiona Apple, Meredith Brooks (of “Bitch” fame), and Alanis Morissette. You know. The singers I eventually listened to.

My Riot shows a bit of this bittersweet ending, but it’s softened by Valerie’s reflection on this thing she somehow became a part of.

“Riot Grrrl. What a great name for a thing,” she says in her narrator’s voice. “I always wanted to be part of something and didn’t realize I was until it was being torn apart. A lot of people just couldn’t understand all these girls with ‘slut’ written on their arms and fire in their hearts.”

In this way, Spears and Helen give a sweet goodbye to a movement that was so fierce, even its name was a primal growl.

If you’d like to learn more about Riot Grrrl, check out:

Girls to the Front by Sara Marcus

Girls Guide to Taking Over the World edited by Karen Green and Tristan Taormino

The Riot Grrrl Collection edited by Lisa Darms

’90s Bitch by Allison Yarrow

“Riot Grrrl United Feminism and Punk. Here’s an Essential Listening Guide.”

“Your guide to the essential riot grrrl films”

The Riot Grrrl Movement: Punk Rock, Feminism, & DIY Culture

God bless libguides… amiright?