We’ve written about a great deal about forgotten feminists in history (I’m particularly fond of Sarah Winnemucca and Florence Price). So here’s another icon to add to the feminist annals of history: Madame Restell.

Born Ann Trow in 1811 in Painswick, England, she came to New York City in the 1830s with her daughter and alcoholic husband. He died relatively short thereafter and Ann Trow was determined to make her own way in her new country.

Reinvention seems to be at the center of any quintessential American dream story and Trow’s is no different. But what seems to us now as a dangerous, political game was fairly ordinary practice in the 1800s — Ann Trow became New York’s most influential, most fearless, and most desired abortion provider and renamed herself Madame Restell.

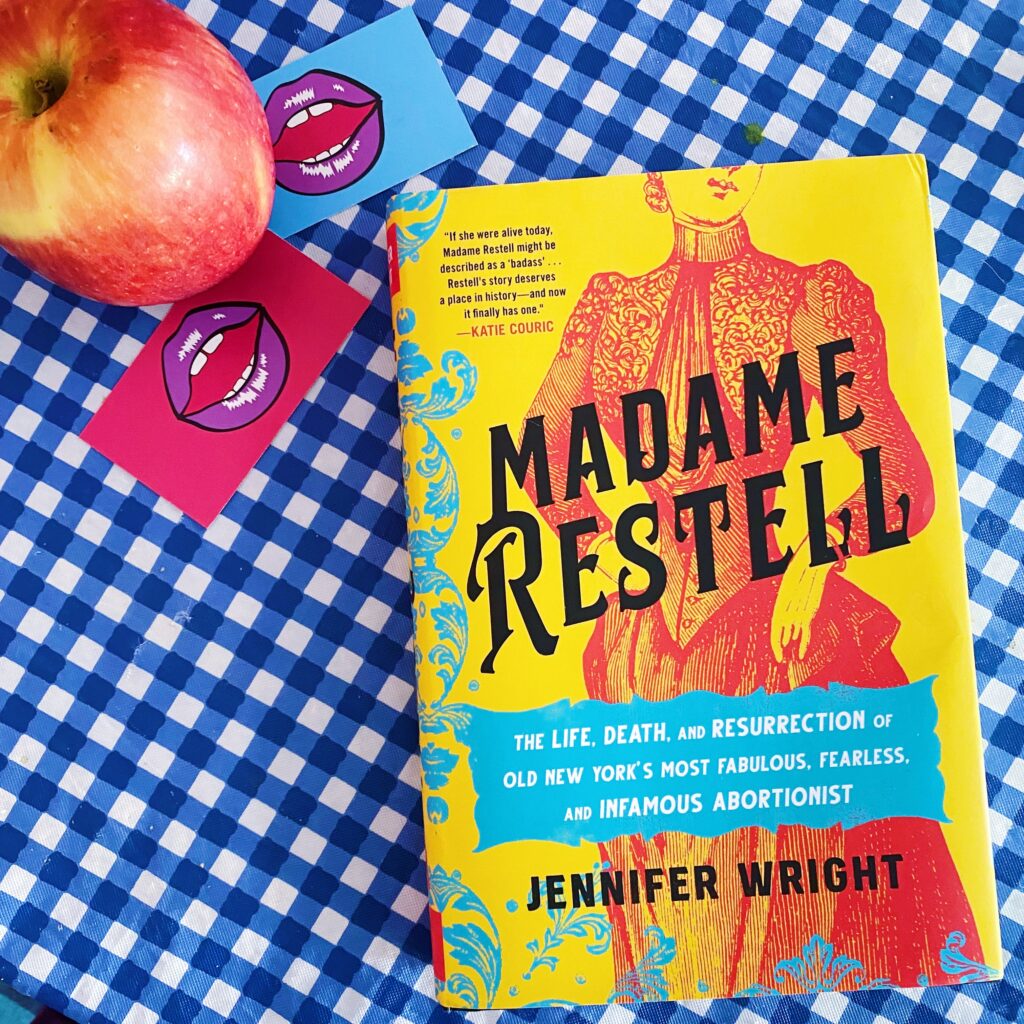

In Madame Restell: The Life, Death, and Resurrection of Old New York’s Most Fabulous, Fearless, and Infamous Abortionist (publishing Feb. 28, 2023 from Hachette Books), author Jennifer Wright uncovers the forgotten history of Madame Restell, helping us see historical precedence to the modern pro-abortion feminist movement. When Madame Restell began providing birth control and abortion services, these procedures were entirely legal. And yet, within her lifetime, she was incarcerated several times, smeared by the press, hunted by powerful men, and publicly sneered at by the same people who would knock on her door when they found themselves “in the family way.” The most egregious of Madame Restell’s deeds? Flaunting her wealth. Of course.

This sharp, witty Gilded age medical history is surprisingly hilarious, ferocious, and easy to read. If you’re curious to know more about one of the United States’ early abortion pioneers and reclaiming the historical canon, pre-order Madame Restell: The Life, Death, and Resurrection of Old New York’s Most Fabulous, Fearless, and Infamous Abortionist.

An interview with author Jennifer Wright

Renee Powers: Tell us a bit about how you came across Madame Restell’s story.

Jennifer Wright: I had initially intended to write a book about the history of abortion, and what a common procedure it has been throught the ages. When that seemed like it was going to be 1,000 page book, I narrowed in on the period in the period in 19th century America when abortion was criminalized.

I quickly found it is impossible to read anything about abortion in America during that period without running into Madame Restell. Her advertisements are constant and she is very clear about how fervently she believes in birth control. She was not only a wildly successful business woman, dispensing pills to induce abortions in multiple cities, but a celebrity. The newspapers are littered with reports not just of her business and her trials, but of her wardrobe, her carriage, her mansion and her parties.

In many ways, she’s such an American success story. Madame Restell started her life in England, working as a maid. She married an alcoholic tailor, convinced him to seek their fortune in America, only to have him die shortly after. She and her toddler daughter lived in New York’s Lower East Side, and it quickly became clear that she could not earn much of a living a seamstress. So, she learned how to compound birth control pills and perform surgical abortions — whch she did without any recorded evidence of ever losing a patient. And she became jaw-droppingly rich. I honestly think it’s the kind of Horatio Alger tale that would appeal to conservatives if she hadn’t made all her money on abortions.

It kept striking me as shocking that her story wasn’t better remembered because, at the very least, in America we love stories about people getting rich doing illegal or semi-legal things. The Wolf of Wall Street. Casino. Scarface. The only two differences are that 1) Madame Restell was a woman and 2) the illegal thing she was doing actually helped people.

RP: Why Madame Restell and why now?

JW: Madame Restell lived in a period where abortion went from being a common misdemeanor in the first few months of pregnancy to literally unspeakable (after the Comstock laws in 1873 banned information regarding abortion and birth control). It’s estimated that around 1 in 5 preganancies during the mid nineteenth century ended in abortion — though the anti-abortion crusader Horatio Storer estimated it was slightly closer to 1 in 4 in New York. Many of those were performed by Madame Restell, or others following in her footsteps.

And she wasn’t shy about the fact that she was performing them. She was profoundly outspoken in her belief that the birth control pills she was selling and the abortions she was performing were social goods — she wrote an article likening birth control to a lighting rod averting the worst ravages of nature that ran on Christmas day. Comstock intended to silence her and women like her.

We can see a lot of parallels in our own time in terms of women’s rights and bodily autonomy being rolled back. We’ve lost Roe vs. Wade. It seems very likely that, should Republicans have their way, there will be a national ban in this country. And there are already efforts to silence people on the topic. In September, for instance, The Chronicle of Higher Education reported that employees at the University of Idaho received a memo “that instructed all employees to remain “neutral” on the subject of abortion. If they could, they should try to avoid the topic altogether, because talking about abortion in a way that could be interpreted as promoting it might lead to felony charges.”

Of course, the Comstock Laws did not stop people from having abortions. An 1898 estimate by the Michigan Board of Health found that, in spite of Comstock’s efforts, 1/3 of the pregancies in the state were terminated by abortion. It will not stop women now, either. But it will lead to women who need abortions being denied medical care for dangerous periods of time. We’re already seeing the results of that as a woman in Texas nearly died from sepsis.

There are also dangers that come with DIY abortions, then and now. The idea that everyone will have access to or use “the abortion pill” (mifepristone and misoprostol) is absurdly optimistic in a country where, as recently as 2015, a woman in Tennessee attempted an abortion with a coat hanger. I imagine as Republicans crack down on the availability of safe drugs to induce abortions at home, we’ll see the consequences of that policy. “The consequences” is my polite euphemism for “women dying.”

RP: In doing your research, what surprised you most about how she was treated?

JW: It didn’t surprise me that people were upset by Madame Restell and her work — and many were. There were plenty people angry that she was performing abortions, and simultaneously angry that she was not performing them for free. But what also surprised me was how flattering reportage about her often was. Everyone agrees she’s so beautiful. There’s one very pervy article by Mordacai Noah where he says she is very bad, and then fantasizes about what her breasts would look like in a prison uniform. When she actually went to prison, she received special treatment from the warden. Not only did the warden’s wife prepare all her meals, and she was exempt from working, but she was allowed to wear her own clothing, so, Noah’s fantasy never came to pass. I expected at least, when she built her mansion, that people would say it was new-money and trashy but every article says something to the effect of “abortion is bad, but this house is stunning.”

RP: What did you enjoy most about the research?

JW: Madame Restell was really funny. It’s infuriating to me that her personal letters seem lost to history, but there are some great moments where people report on her personality. Members of the American Female Moral Reform Society attempted to give her religious tracts when she was in prison, which she rejected, claiming she had enough novels. There are so many wild characters from this period — like Restell’s enemy George Dixon, a man who tried (unsuccessfully) to become so famous as a moralistic newspaperman that “his very hat would become a relic.” Dixon eventually got beaten up with his own hat. Anthony Comstock, meanwhile, was a very guilty chronic masurbator, which might have accounted for a bit of his desire to censor, well, everything. I think we’re often fed a very dry, BBC version of history where everyone behaves with the utmost dignity at all times. We forget that, just like today, history was peopled with figures who were very offbeat and sometimes comical. The more we see the people in history as humans rather than mythic figures, the more we can see how history connects to our own lives.

RP: What can we learn from this important part of history and how can we use it to motivate us in our current fight for abortion access?

JW: I think one of the reasons abortion was able to be criminalized so completely in the mid-19th century is because, occasional figures like Restell aside, very few people were speaking out to defend it. Today, too, we’ve ceded a huge amount of conversational ground to anti-choicers. People are very apt to try to meet them in the middle on the matter of abortion, saying, for instance, that they don’t think you should have “late term abortions” (this is not a medical term). Abortions are generally performed in the last trimester because something has gone horribly wrong. For instance, the fetus may have developed without essential organs. The people who have these abortions are devastated, and largely have them to spare a child a brief life of agonizing pain. So, that’s a bit different from Trump’s claim that doctors “rip the baby out of the womb just prior to the birth of the baby.”

Conservatives are really good at shifting the conversational window to a place where the “middle ground” is very far to the right of where it would have been thirty years ago. And while we’re placating them, they’re shooting at Planned Parenthood, murdering abortionists like George Tiller and jeering at 10 year old rape victims who are now being forced to cross state lines for an abortion. I think we could all use a bit more of Restell’s boldness when it comes to calling out people with ideas that are, at absolute best, misinformed, and at worst utterly cruel.

RP: What are you currently reading?

JW: I try to read fun stuff that does not consist of medical reports from the 19th century in my free time! I’m lucky that some friends have really, really fun books coming out right now. I’m reading The Golden Spoon by Jessica Maxwell, which is just an absolute blast of a murder mystery set at a competition that closely resembles The Great British Bake-Off. Alexandra Petri, is, to my mind, the best humorist alive today. She has a hilarious new book called Alexandra Petri’s US History satirizing historical events in America that makes the fact that we keep repeating history a little less tragic than I usually find it. And Dana Schwartz is following up her NYT #1 Bestseller Anatomy with a sequel, Immortality. It is a must-read for anyone interested in a wonderful love story involving 18th century medical practices and Princess Charlotte.

Thank you to Hachette Books for sponsoring this post. All opinions are our own.