This post may include affiliate links, which means we make a small commission on any sales. This commission helps Feminist Book Club pay our contributors, so thanks for supporting small, independent media!

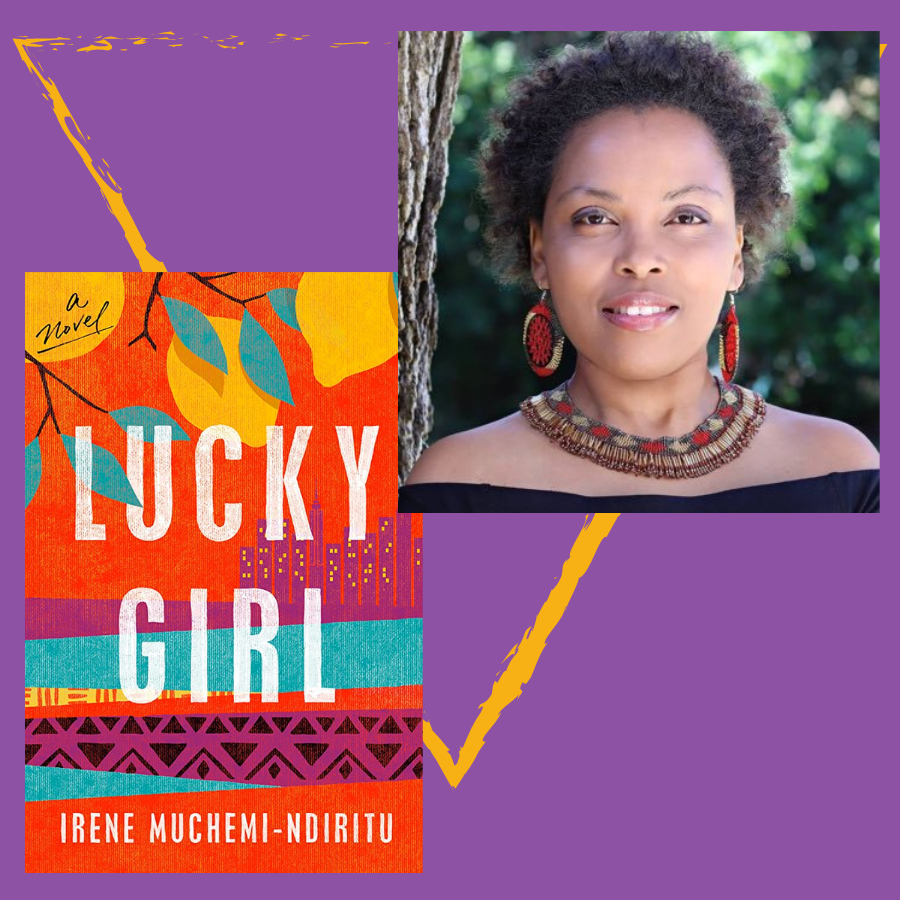

Lucky Girl by Irene Muchemi-Ndiritu centers Soila, a girl seeking independence. She leaves Nairobi for an education at Barnard College. Throughout the story, Soila honors her heart and choices, friendships, and family responsibilities. Soila’s fraught relationship with her mother is a compass for many of her choices and who she becomes.

Book CW: 9/11, abortion, death, racism, mention of rape, abuse, suicide, molestation

My conversation with Irene Muchemi-Ndiritu includes how Soila experiences pain, her relationship with her camera, and conversations between Black Americans and Africans.

What is your definition of feminism?

Only after becoming a wife and a mom twenty years ago did I realize that despite all the strides we’ve made with gender rights, feminism doesn’t exist unless men are feminists. I needed feminist male bosses who wouldn’t penalize me because I couldn’t work around the clock. I needed a feminist husband who’d step up to his share of responsibilities at home and with the kids. I was too afraid to ask for support, yet men feel empowered enough to ask/demand for their needs to be met. So my new definition of feminism is: Empowering women to speak up to men, especially in the workplace; to unapologetically fight against and resist being shamed when they need to step back for mental, emotional, or maternal needs; and to unapologetically demand equal pay.

Soila getting her period was an interesting way to share how she deals with pain. What does pain show Soila?

Soila is so sheltered as a child. She barely has a scrape on her knees because her neurotic mother won’t let her do things that might potentially kill her. The first time she experiences pain is with her period, and this experience is more jarring than it would be for a typical teenager because Soila wasn’t prepped on what to expect. Her period pain foreshadows her unpreparedness for the pain she’ll later endure. Her experiences would traumatize any other person, but for Soila, because she’s so weirdly sheltered, this pain leaves her confused and depressed. But in the end, it emboldens her to stand up and fight for what she wants out of life. Without the painful experiences Soila has endured, she would be a very different character by the end of the story arc, probably still self-involved, aloof, and naïve.

How did you craft the women of the story?

I wanted the women to be organically feminist. I wanted them not to know they’re feminists yet be very progressive in their mentality. Because Soila’s mother never had a strong male role model growing up and was widowed early in her marriage, she learns that she can’t rely on a man to support her emotionally or financially. She’s a strong presence for her younger sisters, so they too, are very independent and want to be successful on their own accord.

One sister is very career-oriented, and two are reliable business partners. Soila’s mother discourages her from needing a man for support and rushing into marriage. I also wanted to show readers that African women can be feminists because there’s a general perception that they are subservient and dominated by their husbands, which is a myth.

Why did you make a camera a relationship for Soila?

She hasn’t got close friendships as a child and a teen. I wanted the camera to become her refuge and her companion.

How do the differences between Black Americans and Africans shape Soila’s point of view? What did you want the conversations to say?

At first, Soila is arrogant and judgmental – almost believing she’s better than the Black Americans. With time she realizes while she doesn’t share their past, she shares their present. She experiences the racial biases they do, and she’s just as afraid and distrusting of the system as they are. She realizes she’s more bonded with Black Americans than with whites.

The conversations are hard and uncomfortable, but the joy of writing fictional characters is they can say all the things real-life human beings wouldn’t have the courage to say. I wanted white readers to understand all the pain Black people carry that they don’t necessarily say out loud to their white friends and colleagues. I also wanted them to realize that Black people may look alike but are very different because of their past traumas.

How does forgiveness play a role in the story’s progression?

Forgiveness comes with maturity. When she’s younger, Soila is all about herself, so she sees the unfairness in her life from the inside looking out. As she gets older, Soila realizes that her mom has her pain, which makes her the way she is. That’s maturity. Only with maturity can Soila understand her mother’s emotional trauma and forgive her.

What organization would you like to amplify?

When I lived in New York, I volunteered for Girls Write Now. At the time, it was still a relatively new organization. GWN is a fantastic nonprofit. It gives girls a safe space to develop mentally, explore their creativity, build a network of friendships that cuts across socio-economic class and race, prepare for college and finally, to get published, which boosts their confidence and shows them that their dreams are valid. Please donate to the organization or volunteer your time.

Thank you, Irene Muchemi-Ndiritu, for speaking with Feminist Book Club about Lucky Girl