I didn’t start reading true crime until recently. Most of the books I flipped through over the years seemed overly lurid and salacious, lingering on the upsetting details of horrific acts that had been committed against female victims who nonetheless seemed blurry and vague, placed there as they were in order to illuminate the inner workings of a monster. And when it came to those monsters — our supposed glimpse at true evil — what I was shown sometimes seemed especially othering.

I remember feeling this way, for example, when I read Mark Bowden’s The Last Stone, about the investigation surrounding the disappearance of two young girls from a shopping mall. As I read, unable to look away despite myself, the girls remained fuzzy in my mind. Meanwhile, Bowden unveiled more and more of the “sprawling, sinister Appalachian clan” suspected to be behind the abduction and possible murder of those doomed girls. The only thing missing were some Deliverance-style dueling banjos.

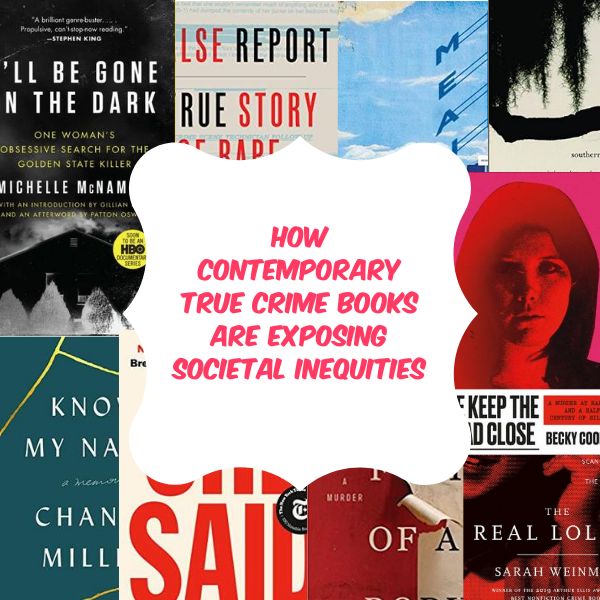

Giving Voice To Survivors’ Stories

Then I read Alex Marzano-Lesnevich’s The Fact of a Body. In this book — which blurs genre lines between memoir and true crime — the author weaves their own story of childhood molestation alongside the case of a man who has been accused of murder.

When the events of this book take place, the author is working at a law firm that defends those who have been charged with murder, hoping to ensure that they do not receive the death penalty. But the author’s beliefs around capital punishment are shaken when this one case reveals parallels with their own past. The author grapples with issues of anger and forgiveness and justice and, in this way, the dark nature of the two crimes in this book recedes in order to hone in on the repercussions for those who have been acted upon.

Since then, other books have leaned into that overlap between memoir and true crime, focusing on the crimes that have been perpetrated upon the authors themselves. In Myriam Gurba’s Mean, for example, the author explores issues of sexual violence, guilt, culpability, race, misogyny, and homophobia. The man who assaults her is pushed to the side in order to make way for the more important narrative around what Gurba decides she owes the world versus what she owes herself as a woman who has been forced to grapple with living life after an assault.

And in Chanel Miller’s Know My Name, the author generously gifts us with a book that answers all of the questions people have ever had about why sexual assault survivors sometimes don’t report what has happened to them. Readers are forced to see exactly what survivors have to go through in the pursuit of “justice” and how that reverberates into the other corners of their lives.

And in this new era of true crime, even those who are no longer with us have been fleshed out as real people — not two-dimensional characters — as in Sarah Weinman’s The Real Lolita, which reveals that the classic novel by Nabokov was, in actuality, based upon the real-life abduction of 11-year-old Sally Horner. The book speaks for Horner in a way she was never able to speak for herself, revealing the lie in Lolita’s portrayal as a nymphet who exists only as a vehicle for Humbert Humbert’s own desires.

Uncovering Systemic Social Inequities

Before I read The Real Lolita and Know My Name, Michelle McNamara’s I’ll Be Gone in the Dark really turned me on to contemporary true crime. Books like hers and T. Christian Miller and Ken Armstrong’s A False Report (which started life as a collaborative investigative article from ProPublica and The Marshall Project and which has since morphed into a documentary series from Netflix) show how women’s stories are often ignored and/or disbelieved, an injustice that is only exacerbated when investigations are mishandled.

She Said by Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey (which I initially classified as narrative/investigative journalism, but which should certainly count as true crime) digs into nondisclosure agreements, and into how they’re used as a cudgel against women who seek to report sexual harassment against powerful men.

Crystal Nicole Feimster’s Southern Horrors revolves around Ida B. Wells and Rebecca Latimer Felton — one Black, one white, but both journalists, suffragists, and anti-rape activists — to show how political power, race, and sex played out in the lives of Southern women.

In all of these examples, the authors’ investigations around horrific crimes are used to uncover something even darker: the systemic inequities that lead to the perpetuation of similar crimes.

In short, these books are not about shock and titillation; they’re about pushing for systemic change. And there’s something irresistible about using writing as a tool to get so damn loud about something that positive change becomes inevitable.

Keep ‘Em Coming!

More recently, I read an egalley of Becky Cooper’s We Keep the Dead Close, a true crime book (out in November) in which the author becomes fascinated by the unsolved case of a Harvard archaeology student who is rumored to have been killed by her professor after an affair gone wrong. In seeking to solve the case herself, however, Cooper also uncovers uncomfortable truths about sexism within academia and about the silencing effect of powerful institutions.

God, it was good and now I’m hungry for more.

![It's our May theme and we're talking about the musical themes that we find in the books we read!

What books do you think we'll be bringing into the Feminist Book Club library this May?

[alt text: white text on a black background: May theme: Music. A boom box is in the center of the image]

#bookstagram #booksubscription #bookish #bookofthemonth #feministbookclub](https://www.feministbookclub.com/wp-content/plugins/instagram-feed/img/placeholder.png)