It’s a room-mance for the books in this tender, steamy story about unexpectedly finding love and being brave enough to let it revise life’s narrative in the final book, Only and Forever, of the beloved Bergman Brothers series.

Viggo Bergman, hopeless romantic, is thoroughly weary of waiting for his happily ever after. But between opening a romance bookstore, running a romance book club, coaching kids’ soccer, and adopting a household of pets—just maybe, he’s overcommitted himself?—Viggo’s chaotic life has made finding his forever love seem downright improbable.

Enter Tallulah Clarke, chilly cynic with a massive case of writer’s block. Tallulah needs help with her thriller’s romantic subplot. Viggo needs another pair of hands to keep his store afloat. So they agree to swap skills and cohabitate for convenience—his romance expertise to revive her book, her organizational prowess to salvage his store. They hardly get along, and they couldn’t be more different, but who says roommate-coworkers need to be friends?

As they share a home and life, Tallulah and Viggo discover a connection that challenges everything they believe about love, and reveals the plot twist they never saw coming: happily ever after is here already, right under their roof.

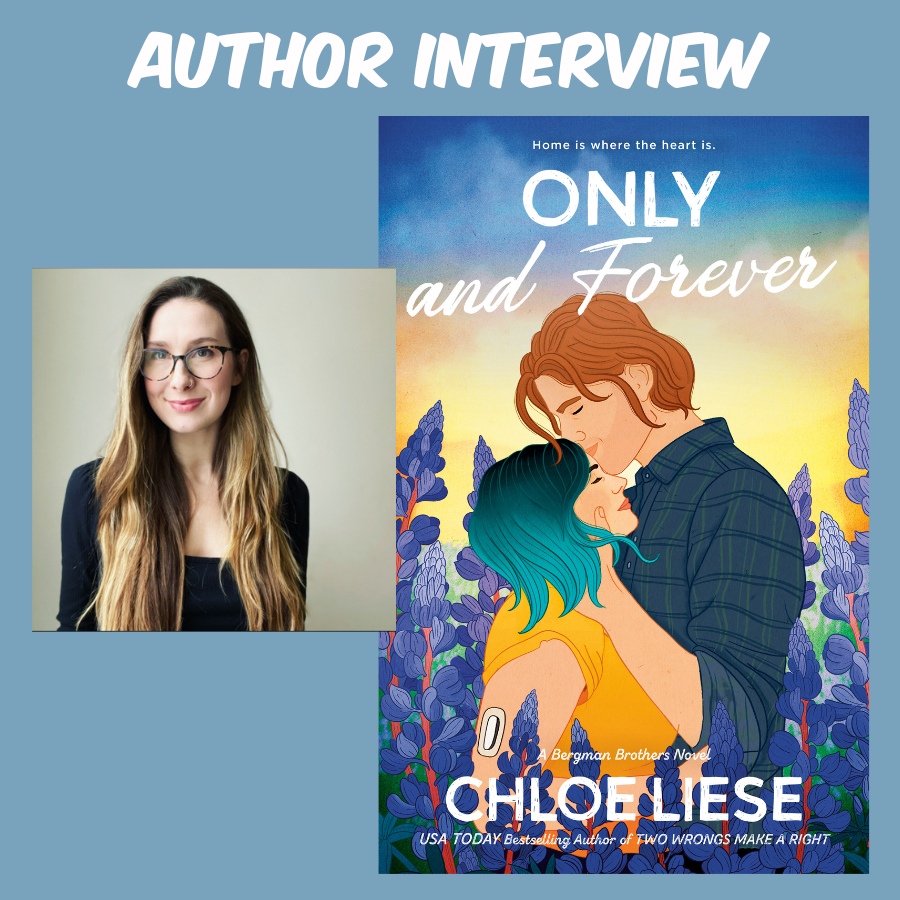

In this interview with author, Chloe Liese, we discuss authentic disability representation in books as well as the important role of therapy in healing from trauma.

How does feminism intertwine with Only and Forever?

I’m a feminist writer, so feminism intertwines with all my writing. Feminism in my stories often bears out in celebrating nuanced female empowerment and also challenging toxic masculinity—I aim to write characters of all genders who do the work to be supportive and loving people and partners. In some of my stories, like my second Wilmot Sister series book, Better Hate than Never—which reimagines Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew by tackling head-on the misogynistic concept of “the shrew” and portraying an empowered, feminist, feisty heroine who is admired and loved for those qualities—feminism as a theme is more overt; in others, like Only and Forever, feminism is simply woven into the very fabric of Viggo and Tallulah as characters and as a couple, and in the Bergman world, itself. In Only and Forever, we see Viggo, a man who has done some serious work to unlearn toxic masculinity and embedded patriarchy—he goes to therapy, is in touch with his feelings and values vulnerability, and believes romance novels are powerful for their capacity to help him (and other men, women, people of any gender identity) grow and deepen emotional intelligence and self-awareness; and we see Tallulah, who is a woman who is self-reliant, confident, and driven, sure of her strengths and proud of her talent, capability, and success as an individual.

What inspired you to write about the love story between Viggo and Tallulah?

For how loud Viggo has been for the past six Bergman books, I knew I had to pair him up with someone who would be just as loud—even if in a different way—someone with firm convictions and an equally intense outlook on life and love. As I thought about how I wanted to conclude the Bergman series, I knew I wanted to be consistent in my efforts as a storyteller to craft a journey that was thoughtfully inclusive, healing and hopeful, playful and passionate, focused on growth and vulnerability and celebrating the many valid forms of love that this cast of characters has to offer each other. What felt different about this story was how “meta” I got—it seemed only right, in spending this much time in the perspective of a romance reader as devoted as Viggo, that we should hear and feel and see his love of the genre, his knowledge of it, his reckoning with the sometimes painful contrast between romantic fiction and the realities of life, born out on page. And in Tallulah, I wrote about a writer, who reckons with how hard it can be to draw from ourselves when we’ve drained ourselves and who learns to embrace the truth that it’s okay to ask for help and reach out for support. I loved the idea of two people who need help in different ways—Viggo with the logistics of his bookstore, Tallulah with her book’s romantic subplot, and show how each in different ways, as they helped each other logistically, they also helped each other emotionally, as they both worked through different wounds that had warped and diminished their hopes and sense of possibility. Between the two of them, I saw a chance to bring Viggo a little closer down to earth, as he realizes real life love might give those romance novels a run for their money, and to bring Tallulah along this path of healing as she’s shown the kind of love she’s learned to distrust, so profoundly and kindly and consistently that she can’t help but open up her heart again. In giving these two a journey as roommates, I saw the perfect opportunity to portray two people who, little by little, gently, patiently, maturely talk and engage and shift as they grow together and evolve, never at the expense of their authentic selves but organically, as they heal and grow and connect and of course, fall in love.

You articulately and tenderly share with readers your passion for portraying characters who have various conditions, illnesses, and diseases, some of which are similar to your own experiences. How can authors ethically and authentically write about the experiences of characters with conditions that are not similar to their own life experiences?

I’m passionate about telling stories that affirm all of us deserve a love story and all of us deserve the chance to see ourselves represented positively and authentically in romances. I do write representation that both resembles and resonates with mine, and while I’m happy to share my approach, I do want to provide a quick caveat: I don’t claim to be an expert on this—just because this is the way I’ve approached authentic, positive representation within and beyond my lived experience doesn’t mean it’s the only way. I will simply say that, as someone who has read stories portraying parts of her lived experience in fiction both poorly and well, I can tell when care hasn’t been taken, and I can tell—and truly value—when authors have put in the work to represent experiences beyond their own authentically, positively, and intentionally. My process has been to represent experiences within my communities—readers I’ve connected with, people am friends with, love and do life with. Before I begin a stitch of writing or plotting, I interview them extensively, then create a character whose life is organically entwined in that experience. Once I’ve written the story, I turn it back over to these authenticity sources and open it up to their critique, then incorporate their constructive feedback. This isn’t about my ego as a storyteller or whether or not I meant any harm or inaccuracy in my efforts; it’s about listening and improving and writing a character they feel is true to their experience. My goal at the end of the day is for anyone who picks up my books, no matter how little or much they see themselves in a character or their experience I’ve represented, to feel like these characters’ journeys are affirming, nuanced, and compassionate, to see a challenge to ableist mainstream culture that teaches us to hide and be wary of entrusting our vulnerabilities and struggles to others. I hope my stories remind my readers that these parts of our lives where we feel most vulnerable can—with worthy, loving people—actually be the most powerful bridges to deep trust, intimacy, and love.

Characters in this book discuss working on themselves to heal from past trauma (a lot having to do with family dynamics) so that they can show up fully in their present relationships with loved ones. What would you say to encourage people who may feel daunted by confronting their past and/or concerned that their past may hinder them from finding their forever person?

To anyone who’s daunted by the prospect of facing their past and its impact on your present through therapy, I’ll say this: I get it; I was daunted, too. And it’s okay to feel that, it just doesn’t mean it has to stop you. Frankly, I think you’re duly prepared for therapy if you go into it daunted—it means you recognize therapy’s power. Therapy leads us down paths that will confront us with the most profound pains, traumas, wounds, losses, and griefs of our lives, but it also takes us to places of such transformative healing, hope, love, and joy that we couldn’t ever get to without that harrowing work that brought us to it. Therapy is hard, but it’s so incredibly worth it. And, yes, it’s wonderful that it can help you be in a healthier place to find yourself in a healthy relationship, but the greatest gain is that you will be able to understand, care for, and love yourself so much better than you ever did; you will feel and forgive and mourn and grow, and it’s so freeing to see who you become in that work—there’s a whole new you to learn and love, and I firmly believe that work must come before we have our sights set on learning and loving someone else (or, if we’re already partnered, it has to happen for ourselves first before we can begin to the work on our relationships, if they are struggling in places, too). The beautiful thing about therapy is that when we know and love and care for ourselves better, we have that capacity for everyone else we encounter. It’s a gift that ripples out in to the world, from our hearts to others. I will never stop singing therapy’s praises.

Thank you so much to Chloe Liese for your time! If you want to read more from Feminist Book Club, you can see pieces on romance genres and feminism, listen to me and Thien-Kim discuss romance through the ages and the gamification of romance and spice. Happy Reading (and Listening)!