This post may include affiliate links, which means we make a small commission on any sales. This commission helps Feminist Book Club pay our contributors, so thanks for supporting small, independent media!

I can’t escape the story of the bad art friend. Again and again, she pops up in the books I read. It’s never quite clear at first which of the two women I’m reading about is the guilty party, but usually she is the one who isn’t narrating.

There is a growing thread in literature wherein an artistic rivalry between women borders on romance, and also often includes layers of theft and jealousy. Two women artists struggle to establish themselves, or they come of age together. They feed on one another, are influenced by each other, and may even take the other’s experiences, images, or words as their own. At least one of the bad art friends is a parasite. And usually, just one goes on to thrive.

In the fall of 2021, the internet was held rapt by the original story of the “bad art friend” (gifted NYT article). Six years earlier, aspiring writer Dawn Dorland donated a kidney. She created a Facebook group and posted about the experience during her recovery. Sonya Larson, a more established writer—who was also a member of the Facebook group, as well as GrubStreet, Dorland’s writing community—later published a story called “The Kindest,” looking critically at a kidney donor and including a letter that Dorland felt mirrored one she had shared on Facebook.

The case of the bad art friend ended up in court, with lawsuits from both sides. Dorland felt her experiences had been repurposed and profited from without her permission, and Larson felt she had been defamed and harassed. The story was everywhere. Journalists and writers across media outlets and platforms weighed in and took sides. Who was the bad art friend? Dorland, for being precious with her experiences? Or Larson, because she used them for her own purpose? Everyone had a take.

I remembered the bad art friend while reading R.F. Kuang’s 2023 book Yellowface. In it, June Hayward steals the unfinished work of her friend Athena Liu and publishes it under her own name. We later find out that Athena engaged in her own kinds of artistic theft.

I thought back to Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels, where Lenu makes art in response to her friend Lila’s talents, and later, as an act of revenge, writes a book including all the details of Lila’s life. In Yiyun Li’s 2022 The Book of Goose, set in the1950s rural French countryside, teenage Fabienne compels Agnés to transcribe her stories and then to take credit for the resulting bestseller. In both of these books, young women write in response to, alongside, and against their friends who are at once the subjects of their girlhood devotion and their competition.

This trope transcends writing. In Zadie Smith’s Swing Time, an unnamed narrator and her best friend Tracey dream of being of dancers, but their talents and their backgrounds differ greatly. In The Art of Vanishing by Lynne Kutsukake, wealthy wanna-be artist Sayako uses Akemi’s actual likeness—including a birthmark she is ashamed to show—in her paintings in 1970s Tokyo.

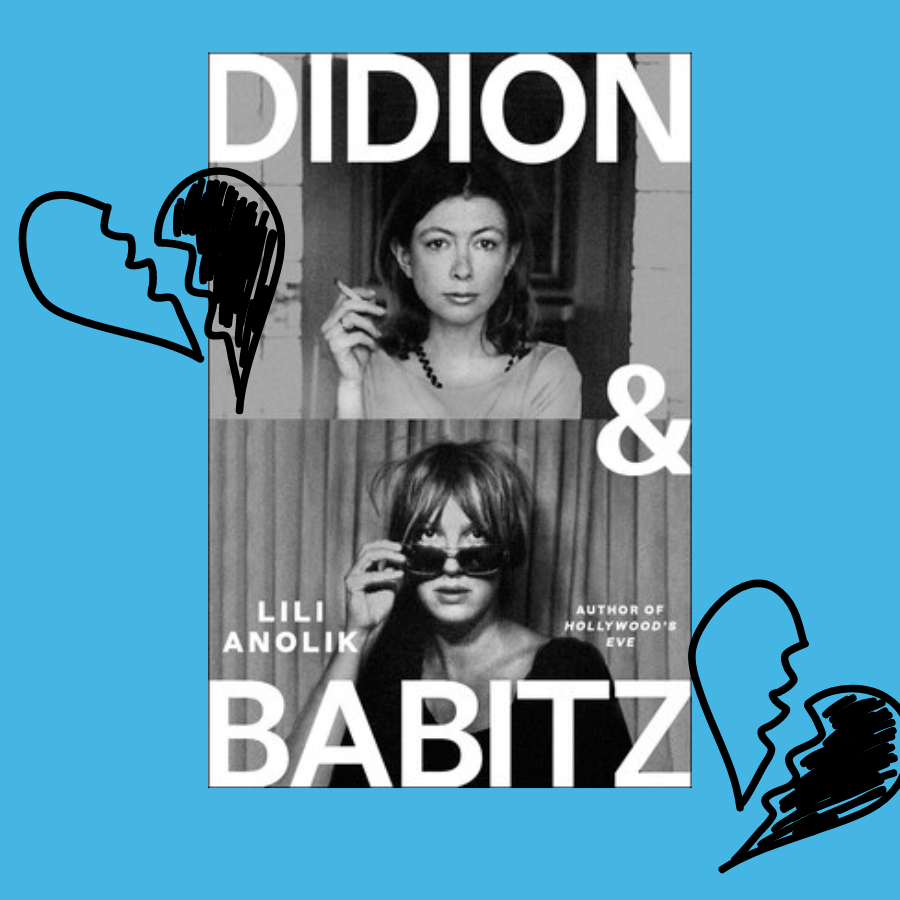

This is the way Lili Anolik depicts the friendship between Joan Didion and Eve Babitz in her new book Didion and Babitz. In 1967, Eve Babitz, bohemian and busty, bumbles into the home of Joan Didion, established, respected, and reserved. In Anolik’s telling, Babitz—lover to Jim Morrison and album cover artist for Buffalo Springfield—is living the L.A. life Didion, a venerated author and former Vogue columnist, can only write about.

Didion is decidedly the bad art friend in this telling. But it is unclear to me from this book whether Didion even kept Babitz around, much less drew from her vampirically. We see Didion through Eve’s eyes, in scraps and snippets of writing. We never see Eve through Didion’s eyes, though. And we don’t see much in the way of Didion’s perspective at all.

Anolik spent years with Babitz and her family working on a 2014 Vanity Fair piece and then a 2019 book, Hollywood’s Eve. This work helped to rekindle interest in Babitz, bringing her a level of fame in her later years that she never rose to during the time she was actively writing. And this book feels like a continuation. It’s a beautiful telling of Eve’s story—full of ups and downs and intrigue—told by someone who has taken real care with her legacy, in a style befitting her. It’s star-studded and gossipy, and full of sex, drugs, and rock and roll. Harrison Ford is seen as a young struggling actor. Steve Martin makes an appearance. It’s utterly readable and fun. But it also felt a little bit like a bait and switch.

In real life, artistic friendship is messy and complicated. Writers may draw inspiration from the same people and places—and from each other. The work of one might provide insight into the life of another, or it may call things we believe we have known or seen into question. Casting Didion as a vampire, without much proof, seems too simplistic.

Didion and Babitz was most interesting—and most lived up to its promise of clarifying aspects about the lives of both women—when Anolik spoke about the ways the two writers’ work mirrored and bounced off one another’s… the way their representations of L.A. showed two sides of the same coin, each reflective of their own experiences: one shiny and one worn down. Which side belongs to whom depends on what angle you’re looking from. Like the question of “who is the bad art friend,” it is all a matter of perspective.