ire’ne lara silva is an Austin-based writer who has authored multiple collections of poetry and short stories. She is a member of the Texas Institute of Letters, has served as Executive Coordinator for the Macondo Writing Workshop / Macondo Foundation (founded by Sandra Cisneros), and is a recipient of a laundry list of awards. This year, she won the Texas Institute of Letters Shrake Award for Best Short Non-fiction.

I came across her poetry back in 2011 as an undergrad. Years later, when her Facebook profile appeared under “people you may know,” the fangirl in me took over and hit ‘request.’ Since then, I’ve been following her writing updates and career. Her writing cuts deep, and she often talks about the things that we as humans try to avoid because of how much they make us feel. It is impossible to read silva’s work without feeling anything.

Recently, her short story Hibiscus Tacos was published as a chapbook by Alabrava Press. The story follows La Muerte who has taken on human form and opened a taco truck in Austin, Texas. It is as interesting and highly readable as the premise promises. I enjoyed reading it very much.

Much to my profound joy, ire’ne kindly answered my questions about her recent releases and writing process.

FBC: How did you come to writing? Or vice-versa?

ir’ene lara silva: I was just talking to a poet-friend of mine about this–wondering how we both, from uneducated Mexican-American families, were so drawn to language and story, to sound and rhythm. I didn’t grow up around books. No one read to me. I hated school but I loved libraries. I loved books. I read them day and night and hid them in every corner of wherever we lived. I read at night, by lamplight, by flashlight, by streetlight when there was nothing else.

Writing came as naturally to me as reading had. I’ve told this story a hundred times–but the first thing I ever wrote was a story when I was 8 years old. I’d woken from a nightmare during an afternoon nap. My younger brothers were asleep, my parents were working, my older sister was watching a soap opera on tv. There was no one for me to run to for consolation. There was no paper in the house, but I found a pen and a brown paper bag from the grocery store. I cut into pages and wrote out the whole nightmare. Something about the act of putting it into words took away my fear and made me feel less alone.

Finding my voice came much later–after I’d graduated from high school in the Rio Grande Valley and went to college in upstate New York. What I consider my first real poem, “Blue Tokens,” is one of the poems in FirstPoems. I read a lot of those first poems at protests and cultural gatherings–which was a very different kind of audience to learn how to read my work for, as opposed to at open mics or poetry slams.

FBC: Hibiscus Tacos beautifully celebrates Mexican culture, amazing food, femininity, and love. What brought you to write the story from the perspective of La Muerte?

ils: I watched the movie Book Thief years ago, and I absolutely loved the fact that the narrator was Death. I kept thinking of all the story possibilities, but nothing quite took off until I thought about Death not being just the narrator but the main character. Then it was just a matter of gathering the guts to write from Santissima’s point of view. As time passed, the idea kept drawing all of these other things I wanted to write about–a memorable hospice nurse, my experience with my mother’s death, my love of Los Panchos and reggaeton and really good tacos and Austin culture.

I started writing the story in the first few minutes of 2020. I was in a weird period where I couldn’t seem to write at home by myself. I kept meeting with friends to write in coffee shops and restaurants. I invited friends to join me on December 31, 2019 at 10pm at an Austin cafe so we could write ourselves into the new year. The plan was to write till dawn and then go find some breakfast tacos, but we were all too tired to stay up all night and gave up around 3am. But there was something about writing with other people that made me brave enough to write Santissima.

And then the pandemic started and the streets of Austin emptied and all the cafes/restaurants closed down. There was nowhere to write but home and no one to write with. And the awareness of mortality was everywhere. Of course, that was also when the story shifted to another tone and when I realized that it was going to be a love story after all.

FBC: When you’re writing stories, what usually comes first: the characters or the story?

ils: Characters always. I usually have no idea what the story is going to be. It’s a voice that draws me in–whether it’s the main character or some nebulous narrator-voice that starts speaking. My hope is that if it’s compelling enough to draw me in, it’ll be compelling enough for my readers.

I don’t know that I would advise anyone else write the way I do–I discover the story as I go. I also don’t especially feel obligated to have a plot or dialogue or descriptions. Sometimes to get at the heart of what’s speaking to me, I have to just sit and listen and forget everything I ever knew about how time or reality works. In the beginning, I’d write stories like they were patchwork quilts and I was color-blind and didn’t have a plan for the pieces and like I had to learn how to write again every day. I’m not sure that I’m any better now. Friends of mine talk about writing thousands of words a day. At the moment, I’m happy with the story I’m working on if I progress with six sentences every few days.

For more than twenty years, I’ve both consoled myself for my slowness and pushed myself forward with a quote from the writer Jeanette Winterson: “The artist does not turn time into money, the artist turns time into energy, time into intensity, time into vision. The exchange that art offers is an exchange in kind; energy for energy, intensity for intensity, vision for vision.”

It has never been productivity or prolificity that I’ve been looking for or working towards.

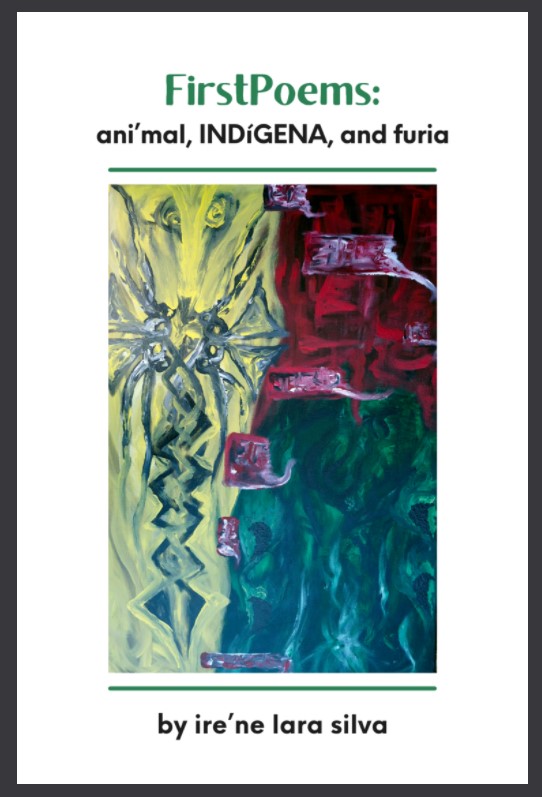

FBC: Your most recently released collection, FirstPoems, contains your poetry from 1994-2010. As a poet and writer, what is it like to see your work across a number of years and periods in your life compiled altogether in one place?

ils: It’s crazy to be able to introduce a poem and say, “And I wrote this one 27 years ago.” Crazy to think how much of my life has gone to writing and reading my work. But at the same time, it only seems right because that’s all I’ve ever wanted to do. And I’ve written while working multiple jobs most of my adult life—jobs that had nothing to do with writing and jobs that never gave me time for writing and jobs that drained all of my physical and mental energy. I’m a little less than three years away from retiring from my full time job, and I’m definitely counting down to that magic date where I’ll dedicate myself wholly to my writing.

I’ve heard a lot of poets and writers say their ashamed or embarrassed about their first work, but not me. I can’t help but think of my first poems with tenderness. They’re where I started, they’re how I learned to inhabit my own voice, they’re what got me here—without those first poems I wouldn’t be where I am now.

I posted one of these poems a few years ago on social media, and a friend of mine said something about how the poem belonged in a Chicana museum. That made me think about how difficult it would be to find my first poems. My first full length collection, furia, was out of print, and there were never more than about a hundred copies of each of my self-published chapbooks. So I reached out to FlowerSong Press—and it all just came together so smoothly. I love the book we made together, and I’m so happy FirstPoems is out there now—and that my first poems are being read by many for the very first time!

FBC: After reading many of your poems, and even Hibiscus Tacos, I can only describe what they evoked from me as achy and empty, as if my emotions had been scooped out. I cannot imagine how challenging it must have been to write them. How do you balance practicing self-care while also giving so much of yourself to your work?

ils: My thinking about writing has changed so much over the years. When I was a kid, writing was about escaping life, my family, violence, and abuse. As a kid, I could never write enough. Later as an adult I came to writing to express myself, to connect with my culture and history, and to engage with community. Still later, I realize that I had to reimagine what writing was because I liked my life and I no longer needed to escape it. Writing became about finding a way to more fully be in the world, in my life, in my heart. It wasn’t until after the publication of my first full-length collection, furia, that I learned that writing was about something beyond myself, that it was about creating dialogues with others and between others.

I tell people I cried all the way through the writing and revising of my first three books, furia, flesh to bone, and Blood Sugar Canto. It wasn’t until I came to Cuicacalli/House of Song that I learned what it was to write with joy, from joy. And that continues into the writing I’m doing now. As it turns out, it’s not about subject matter—because there’s still grief and loss and violence in my work, but there’s also so much more. The joy comes from having worked and written myself into a freedom I’ve never known before. Into an understanding of writing that I’ve never had before.

What I understand now is that writing has become a deep medicine for me. I don’t have to recover from writing—writing is my healing. On my part, the hardest work is to keep myself open to receiving it and to knowing my limits. I have friends who write thousands of words every time they sit to write. The story I’m working on now is being written six sentences at a time. And I don’t write multiple times a day. I don’t write every day. Productivity, schedules, outlines, deadlines—none of those things really matter to me. Intensity is important to me. Vision is important to me. Imbuing my language with energy is important to me.

I also think about the question posed in one of Toni Cade Bambara’s novels: “Are you sure, sweetheart, that you want to be well?” Perhaps, six sentences of healing at a time is the appropriate amount of medicine for me at this time. Experience has taught me not to insist—only to invite. To prepare. To give myself to my work. To shape it with all of the heat I can give. To surrender and to wrestle at the same time.

Writing tends to be mostly physically tiring to me now. I deal with chronic pain and my body can only stand to be at my desk for so long. My body tells me when it’s time to rest. But I move away from my desk feeling as if there is wind in my hair and light in my eyes. I feel a lightness and a gladness in my heart that wasn’t there before.

In this culture, we tend to think of art-making and writing as being tied to destructive impulses and habits—alcohol, drugs, abusive relationships, etc. What would it be in our lives to return to a different understanding of what art-making is? One related to healing and health and setting the physical/emotional/psychological to rights?

FBC: What are you working on right now?

ils: Right now, right now, I’m working on finishing what will be my second collection of short stories, titled, the light of your body. I’m 10 stories in with 3 to go. The stories are concerned with the intersections of art-making, spirituality, desire, and healing the wounds of the conquest.

After that I’m getting back to the novel I started working on 15 years ago that’s set mostly in the Rio Grande Valley. And I’m starting to get little flashes of what will be the next poetry collection

I’m hoping that things will work out in that orderly fashion—but anything could happen.The last time I was really making progress on the novel, I got surprised by all the poems that became my third book of poetry, Cuicacalli/House of Song. But what can you do? You have to follow the urgent voices.

FBC: Something we love to ask at Feminist Book Club: what are you reading right now?

ils: Last best book of poetry I read was Heid Erdrich’s Little Big Bully. Currently reading Cesar L. DeLeon’s speaking with grackles by soapberry trees. And I’m being blown away by the gorgeousness and profundity of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass (We’ve talked extensively about Braiding Sweetgrass and our conversation with Robin Wall Kimmerer here).

To learn more about ire’ne lara silva, her work, and upcoming events, check out her website.