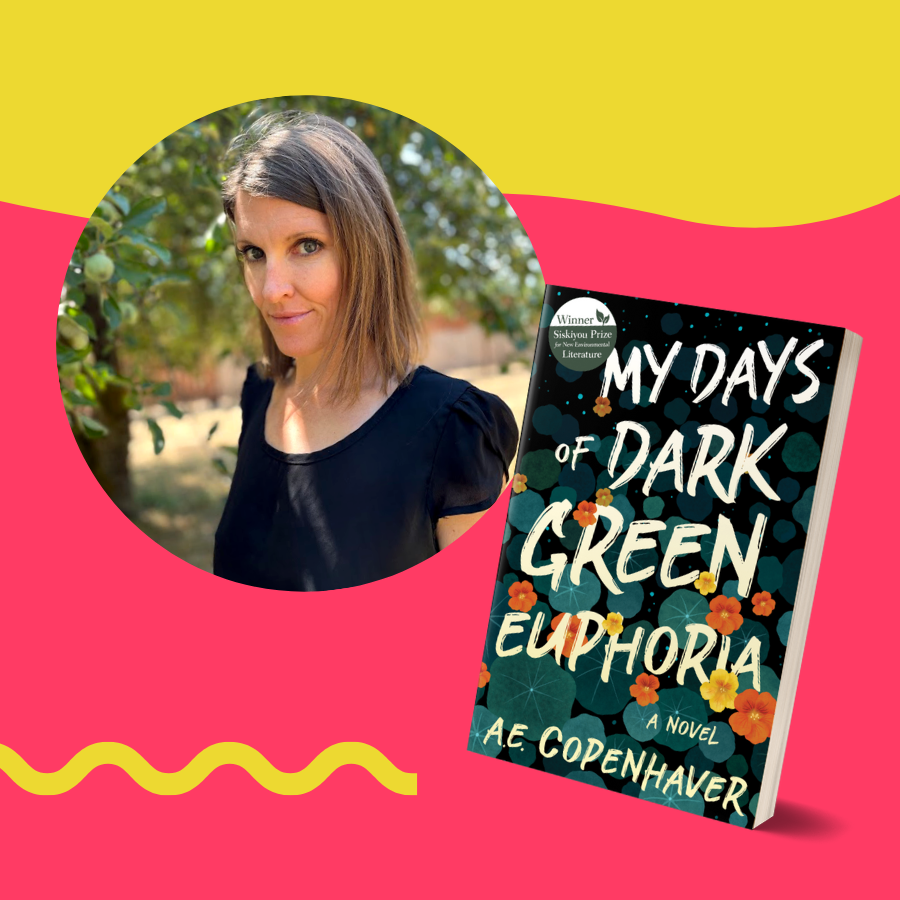

In A.E. Copenhaver’s debut novel, an overwhelmed environmentalist named Cara finds unexpected—and ethically questionable—relief in her boyfriend’s carefree mother Millie. My Days of Dark Green Euphoria is simultaneously a wild ride of an adventure tale and an important exploration of eco-anxiety in our modern world. I spoke with A.E. Copenhaver about what led her to write the novel (which won the 2019 Siskiyou Prize for New Environmental Literature), the importance of representing eco-conscious characters in general, and, of course, rage.

After reading this book, I was on vacation and I kept having moments where I’d think, “Oh no, I’m being such a Millie right now!” (For example, sipping a cocktail with a wasteful umbrella in it or purchasing coffee in a single-use cup.) I assume that’s part of the goal of writing an eco-novel—to stick in people’s minds and help them think about their choices? You’ve created this fun spectrum with Millie on one end and Cara on the other, and I think everybody falls somewhere in between.

Totally. And it’s fun because both Millie and Cara are really over-the-top versions of themselves. Millie is a really over-the-top version of someone who just doesn’t have any care in the world, doesn’t read the news, doesn’t have any concept that she’s connected to the wider world. And Cara is crippled with the burden that she places on the world and on the people and animals around her. It was really fun to play with both of those caricatures. If you’re someone who lives your life like Cara, you look at everybody else and you see them like Millie. But Cara’s just outrageously judgmental.

The book opens with Cara wondering if she can really be in a relationship with someone who kills spiders—a seemingly benign and common occurrence for many people. Why did you choose the spider kill to set the tone?

The spider scene as the opening scene really sets the reader up to think, “Oh, okay, we’re dealing with somebody who’s looking at the world in a completely different way.” Could you imagine what your life might be like if every time a fly came by you and you grabbed your fly swatter, you felt that you were taking someone’s life? There’s that conversation where Cara and her best friend Renée are talking about spiders and Renée’s sort of like, “I get it, Cara, spiders are people too.” So, that’s the premise. How does your perception of the world change if you’ve expanded your understanding of who someone is beyond just, you’re a human being and you have a brain? How does your vision of the world change with those more expansive parameters in place, when “someone” may be a non-human or more-than-human person or entity? That’s what the novel explores.

What led you to write this book? Do you share any similarities with Cara?

I’ve been an angry version of an environmentalist before. I’ve been that person who looks at the world and is just angry and outraged. I’ve had less-than-productive conversations with people in my life before, where I took the holier-than-thou approach and that just did not work. I think a lot of people who care about the planet have been that person at some point or another. It doesn’t have to be about the environment; it can be about any social justice issue. If you really care about something, you get this kind of rage that comes along with it. I grew out of that phase and into a more productive way of being in the world, but the caricature of Cara stuck with me. I wanted to play with that anger and that rage that she has because I do think there’s value in that perspective. Some people read this and they’re appalled. They’re like, “Oh my gosh, there’s nothing redeeming about her, she’s just awful,” but it’s supposed to be over-the-top. This is not supposed to be a morbid, somber treatment of eco-anxiety, even though Cara has some serious issues that she’s dealing with. It’s meant to be portrayed with a lightness and absurdity that might soften it for people.

I actually really appreciated reading about a vegan environmentalist character who is just unapologetically frustrated and angry.

The question of vegan literature is really intriguing to me. How have vegans or vegetarians been portrayed in literature? Often they’re not. And if they are, they’re stereotypically weak or tired or pale or whiny. I thought, as a vegan, it would be fun to take on these stereotypes and parody them myself. It’s almost like you can’t have a sense of humor if you’re a vegan—the world’s just too sad and serious. I definitely don’t think that’s the case, and I think humor and satire play such an important role in our envisioning of different ethical perspectives.

What makes this novel a feminist read?

It didn’t occur to me until after I had written it that it passes the Bechdel Test, which is funny to me because it just seems like such a low standard, right? Just two people, maybe they have to be named, they have to be talking about something other than men. So, on a superficial level, obviously it passes the Bechdel Test. It’s also a feminist read because Cara is not too fussed about the male gaze. She’s not immune to it, she thinks about beauty duty and things. But most of the time she’s just living her life. That is an important feminist component of it—the idea that we can live in the world as human beings without having to think about how the dominant culture is perceiving us. That’s not to say that to be a feminist character Cara must be categorically unlikable or offensive, but rather, readers are more prone to deem a character unlikable or offensive if she doesn’t comfort or cater to their own world view. In telling her story, Cara is certainly not catering to anyone’s world view—how she critiques the status quo, the dominant culture, isn’t always pretty or pleasant, but there’s still value in considering her perspective.

Cara pokes fun at superficial “self-care” routines. What does real, meaningful self-care look like for someone at risk of this kind of serious compassion fatigue or burnout? What could Cara have done to prevent herself from getting to this point?

Cara’s not really great at taking care of herself. She needs better boundaries, and she needs that self-awareness to know when she’s getting to the point where she’s not going to be able to recover, or that she’s going to go off the edge and make decisions that harm herself or her values. Self-care is so wide-ranging, so it’s hard to say what one person might need. But there are so many resources now for activists and for advocates. These are becoming more common. Cara would do well to use those and to look into some better coping mechanisms.

What do you hope readers will take away from reading this book?

I hope that they read this book and consider Cara as a character and as a window into another ethical perspective. I think a lot of people read this book and feel judged. They feel like they’re being judged by Cara—and that’s fair. But I actually think the book is about Cara being concerned with herself and her experience, so I want readers to interact with that. Why is she making the decisions she’s making? Why is she a good character? Why is she a bad character? I hope readers will engage with it on that level as opposed to feeling judged. Because my hope was to provide a fascinating insight into another way of living on the planet.

Follow A. E. Copenhaver at her website, Instagram, and Twitter!

Editor’s Note – I would recommend listening to my review & interview with Layne Fargo, author of They Never Learn, and the general trope of unlikeable characters as well as Tayler’s review of She’s Unlikeable as we consider the TYPE of female characters we’re consuming in literature.