Our theme for January was Feminism 101, a chance to refresh our feminist practice at the start of a new year with the book Women’s Liberation! Feminist Writings that Inspired a Revolution & Still Can. (Personally, I plan on working through it throughout the year; it is quite large.)

Keeping with the theme of going back to feminist basics and focusing on books that should be filed under essential reading, I decided to turn to the work of a prominent feminist to kick off 2023, and one of the first names that came to mind for me was Audre Lorde (1934-1992). Lorde was a writer, radical feminist, and professor who dedicated her life to civil rights activism. For her, feminism was nothing without acknowledging racism, misogyny, sexism, homophobia and other problems that marginalized communities face.

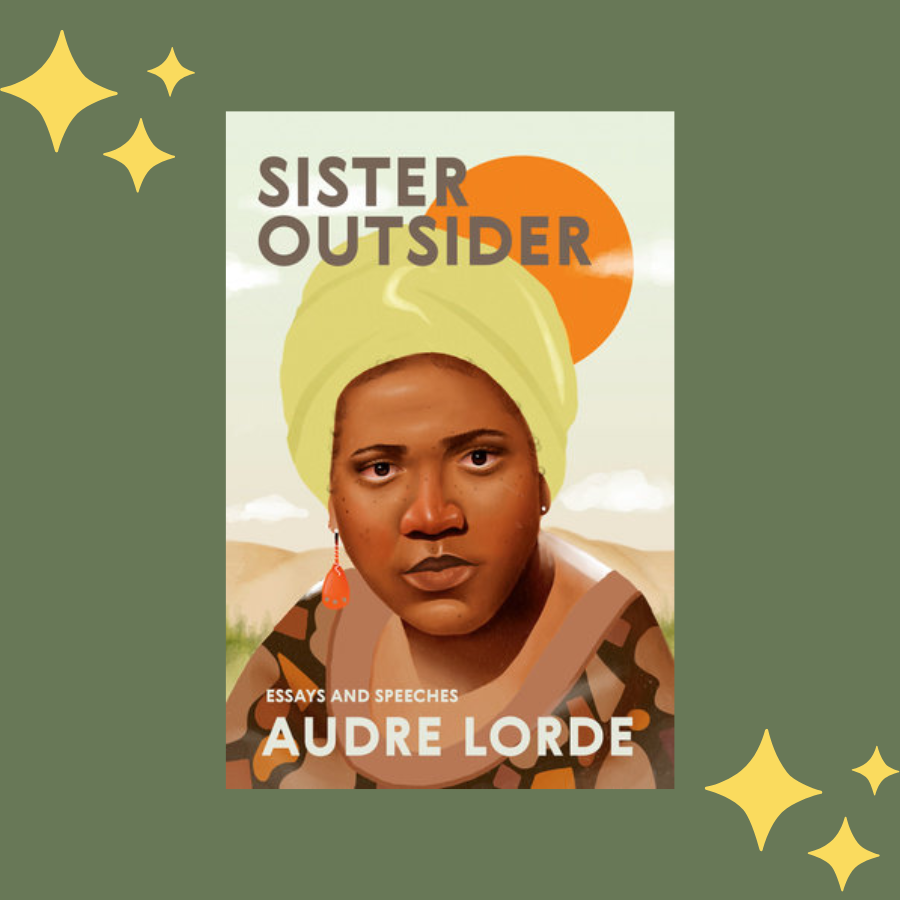

I’d only read a couple of her essays and a handful of poems in college, and although I’m familiar with the general gist of her work, I realized I needed to remedy this with reading one of her works in completion. I picked up Sister Outsider and quickly found it’s hard to read without a pencil or highlighter.

I cannot purport to be well-versed enough in Lorde’s work to adequately analyze it; I need to read more to attempt that. Nevertheless, I’m walking way from Sister Outsider with two things: 1) Audre Lorde not only gives us the big ideas, but she also provides us with a framework for working through big ideas in her essays. 2) I am inspired and convinced that, like Cheryl Clarke who wrote the foreword to the 2007 edition of Sister Outsider, I’ll need several copies for bedside and office, and also another to lend out to others. Here are some more key points that I picked up from my reading.

Audre Lorde wrote and worked from her identity at all times.

Lorde almost always introduced herself as “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet” in her writing and at presentations. Her work is rooted in her experiences of the world in the context of these identities. She often wrote about racism and misogyny as she “usually found [herself] as a part of some group defined as other, deviant, inferior, or just plain wrong.” She also wrote about motherhood and her work. Her daily life informed her writing. In so working from a place of understanding of herself and her intersecting identities, Lorde also spoke (and still speaks) to a larger audience.

She also focused on promoting the work of others during her lifetime. In 1980, Lorde and other feminist writers founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color press, an activist feminist press that focused on uplifting the work of women of color from all backgrounds, identities, and sexual orientations. Although the press went inactive when she passed in 1992, its legacy as the first ever press run exclusively by women of color is timeless.

She leaned into her feelings.

An excellent point that Lorde makes in the essay Poetry is Not a Luxury is how the patriarchy seeks to divide and categorize. It is not enough for a person or an idea to be muti-faceted, or for more than one thing to be true at once.

For Audre Lorde, poetry is a way of understanding our feelings and cultivating a fertile space for new ideas:

“But as we come more into touch with our own ancient, non-european consciousness of living as a situation to be experienced and interacted with, we learn more and more to cherish our feelings, and to respect those hidden sources of our power from where true knowledge, and, therefore, lasting action comes.”

In addition to our emotions leading to new ideas, Lorde sought to use them to channel productive action as well. In The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism (first a 1981 keynote presentation, later published in essay format), Lorde set forth the idea that anger can become a tool if we channel it in the right way.

She called out problems that are still prevalent today.

In an open letter to Mary Daly, Lorde lays out the divisions in the lesbian feminist community of the time between Black and white women, as illustrated in the way that Daly excluded Lorde in her book, Gyn/ecology. Daly, a radical feminist philosopher and theologian, used Lorde’s words in her work only in a section focused on genital mutilation. Lorde called her out for this in her letter, and also pointed out that she could have cited her words in any other section, because there were plenty of connections in their work at the time. It is clear that Daly did not actually read Lorde’s work, when Lorde had found meaning and connection in Daly’s. On top of that, Daly didn’t even respond to her letter; Lorde shared it publicly four months after sending it after not hearing back. (Can you imagine ignoring Audre Lorde? How embarrassing.)

Through a single letter, Lorde eloquently and efficiently explained an issue in the feminist community that dates back to the very beginning and that still persists today: the exclusion of Black women’s voices in feminist spaces by white feminists. While Lorde may not have been the first to point this out, she is definitely not the last– in her 2020 book Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women that a Movement Forgot, Mikki Kendall touches on this exclusion. “When feminist rhetoric is rooted in biases like racism, ableism, transmisogyny, anti-Semitism, and Islamophobia, it automatically works against marginalized women and against any concept of solidarity.” The impact and reach of Lorde’s work is immeasurable, but we’re able to see it in the work of contemporary Black writers. (Note: We featured Hood Feminism in an FBC box previously as well.)

Final Thoughts

My copy of Sister Outsider has got random sticky notes in different places and is all marked up. I look forward to revisiting it and engaging with the text some more. Next up, I’m interested in The Black Unicorn, a poetry collection and The Cancer Journals, a collection of writings around her breast cancer diagnosis. I’d also love to get my hands on The Selected Works of Audre Lorde (2020), edited and with an introduction by Roxane Gay.

![On this episode of Feminist Book Club: The Podcast 💞 Sometimes we just wanna gush about the things we love.

For Renee (@reneethebookbird) and Margot (@neonmargot), it’s hardboiled fiction. For Ashley (@driedinkpen) and Nox (@nox_reads), it’s Lady Gaga’s new album. Tune in for two conversations around why we love the things we love.

Find this episode of Feminist Book Club: The Podcast anywhere you listen to podcasts or stream on our blog!

[alt text: Hardboiled Lesbian Fiction + Lady Gaga's Mayhem]](https://www.feministbookclub.com/wp-content/plugins/instagram-feed/img/placeholder.png)