(cw: marital rape, suicide)

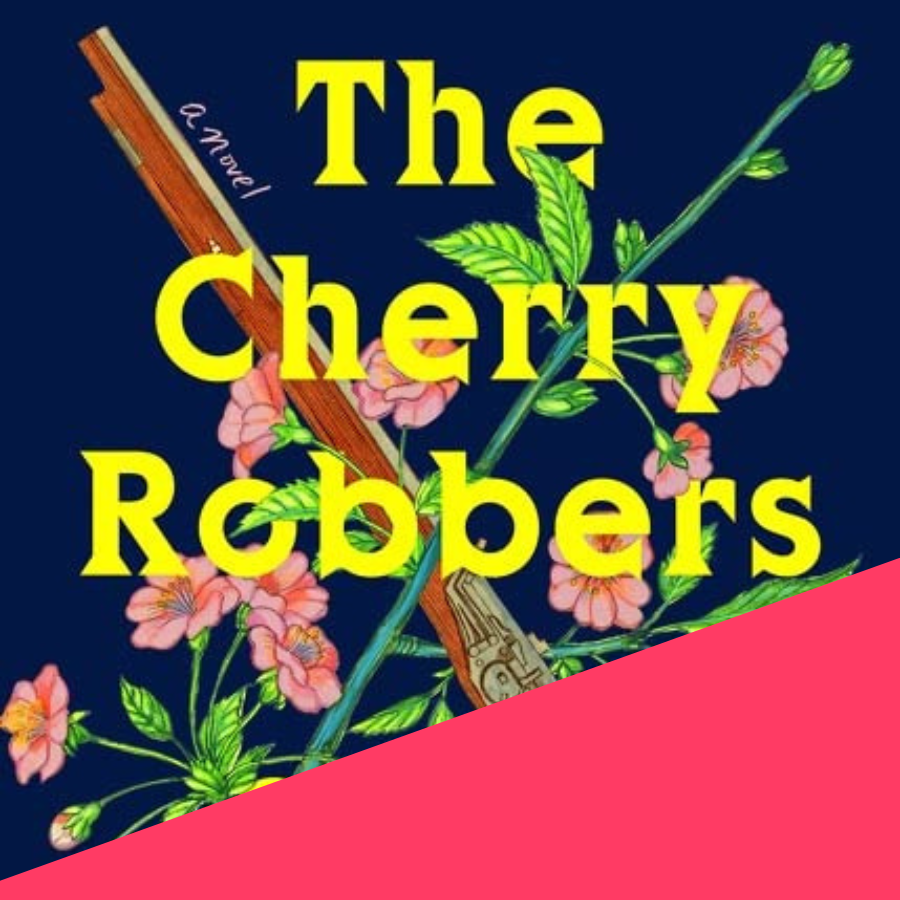

I’m such a sucker for a floral book cover, and the cover for Sarai Walker’s The Cherry Robbers does not disappoint. Cherry blossoms splay themselves out across a lush, deep blue background, one long stem crisscrossed with a rifle. Bright yellow text floats on top. It’s gorgeous and eye-catching and it’s what drew me to the book in the first place.

The synopsis drew me in even further. After all, I’m also a sucker for dark fairytales and gothic horror. Ghosts that may or may not be there. Terrible curses.

Walker’s book? It has all of this in spades.

But this book quickly revealed itself to be so much more.

Before I get into that, though, here’s the quick and dirty lowdown: Six sisters grow up together in a palatial home paid for by their father’s firearms fortune, sequestered from the rest of the world, waiting for marriage to save them from their isolated existence. Their mother spends most of her time locked away in her bedroom, muttering about the ghosts of those killed by the Chapel family firearms, leaving the raising of her children to the hired help. Their father is distant. They have only each other.

Then the eldest sister becomes engaged and their mother has a premonition that something terrible will happen if her daughter goes through with the wedding. She is ignored — dismissed as mad — but soon, a terrible pattern begins to emerge as one sister after the other dies horribly immediately following their wedding night.

One sister, however, manages to escape this fate. Our plucky narrator. But will the past catch up to her anyway? Dun dun DUNNNN.

The Restrictive World of The Cherry Robbers

The tragedies at the heart of The Cherry Robbers begin in 1950, a time not known for its liberties (not for women, anyway).

But the book itself opens in 2017 with the reclusive artist Sylvia Wren, who lives in New Mexico with her partner, making art and avoiding the media.

As self-isolating as our narrator is, her life feels expansive to me, perhaps because it is fully her own. In fact, I want to linger with her there, learn about how she came into her success… what her life is like. But she soon receives a letter from a journalist who purports to know about her past: namely, that she is not Sylvia Wren at all but, rather, Iris Chapel, heir to a firearms fortune who went missing years ago.

As Sylvia/Iris considers her next move, we are thrust into the past.

This recounting of the past is the meat of The Cherry Robbers, and reading it feels just as claustrophobic as life in the Chapel household must have been. In fact, as I am pulled through the Chapel family history—the eldest daughter’s engagement… the mother’s premonition… the deaths that follow—I begin to forget about the things that drew me to the book in the first place. The ghosts. The mysterious curse. Rather, I start to see that what Walker is really exploring are the ways in which the heteropatriarchy controlled women in the 1950s, and how that mirrors the ways in which we continue to be controlled today.

The Myriad Ways in Which Women Are Controlled

I hate spoilers so much, but it’s hard to enumerate all of the ways in which women are controlled in this book without including some.

So consider this your SPOILER WARNING.

Forced childbirth, marital rape, accusations of hysteria, and forced institutionalization

Belinda, the matriarch of the Chapel family, comes from a long line of women who died in childbirth. Belinda, however, manages to survive the births of her six daughters, who are the product of continued marital rape at the hands of a man she was forced to marry because she was unable to support herself. After all, at that time, there were not many employment opportunities for women, and most were raised to get married, pop out babies, and run a household.

Throughout the book, Belinda is kept hidden away so that her family doesn’t have to be inconvenienced by her screams or disrupted by her dark premonitions. Even when the things she hints at come to pass, she is still disbelieved and, eventually, institutionalized.

Though the Chapel sisters are the centerpiece of this book, it is poor Belinda—shoved away into the background—who best illustrates the numerous ways in which women were once constrained. It’s a smart choice on Walker’s part because, with Belinda relegated to secondary status within the narrative, the commentary on these pernicious forms of oppression doesn’t feel as heavy-handed as it might have otherwise.

Marriage as the natural path for women

Where Belinda was forced into marriage, the Chapel sisters (most of them, anyway) yearn for marriage as a means to an end… an exit from their isolated existence, one in which education for the purpose of a career is frowned upon.

And how else are they expected to feel? They were raised to believe that this is the way of things. Even as things turn dark, and despite the over-the-top signs that marriage is not as magical as they were led to believe, they still want that prize at the end of the rainbow.

But is this really the lesson we’re meant to draw from the text? Sure, five of the six Chapel sisters perish. But not all of them go through with a wedding. The true villain in this arc seems to be the loss of virginity (does the title of the book refer to the popping of one’s cherry? … is that too on the nose?), women ruined by their sexuality. But considering that the concept of virginity is a meaningless social construct—and that a popped cherry (a torn hymen) can present itself with or without sexual activity—I’m skeptical and mildly confused. What are we to infer from the curse at the heart of The Cherry Robbers?

Repressed queerness

Then there are those who shy away from the idea of marriage… who, in fact, are not interested in men at all. I include this here because the book does show how those who did not fall within the bounds of heterocentric norms were not allowed to live their truths out loud.

Interestingly, it is the queer awakening of the main protagonist—and her embrace of this queerness, her running toward it—that ultimately saves her.

Here, the book risks falling into the trap of presenting a simplistic takeaway: Men Are Bad.

But I prefer to interpret her storyline as a queering of all womanly expectations of the time. Yes, Iris Chapel eventually comes to realize that she desires women. But her greater rebellions lie in believing her mother when no one else will, leaving home as a single woman, pursuing a career as an artist, and eschewing the life of the Happy Homemaker.

The More Things Change…

It’s impossible not to read The Cherry Robbers as a commentary on the revocation of many of the rights women and LGBTQ+ folks have fought for and won over the years.

For example, we still live in a time when heterosexual marriage is considered to be the end game for women, where careers are placeholders for the things that will truly matter later on: marriage and motherhood.

We still live in a world in which queerness is suppressed, in which anti-trans legislation and Don’t Say Gay bills abound, in which gay marriage hangs on the precipice.

We still live in a world that paints outspoken women as crazy, where involuntary hospitalization is still a thing, and where loopholes to spousal rape laws exist.

And most recently, of course, we still live in a time of forced childbirth, especially so after the fall of Roe v. Wade.

The Cherry Robbers may read as historical fiction… but aren’t we still right there?

In finishing this book, I questioned the overarching takeaway… the meaning behind the curse that plagued the Chapel sisters. And I wished I could have seen more of the story that bookended the novel: Iris becoming Sylvia. Her life outside the Chapel stronghold. Her blossoming.

But on the whole, I enjoyed this exploration of feminine oppression, and the story of the woman who broke free.