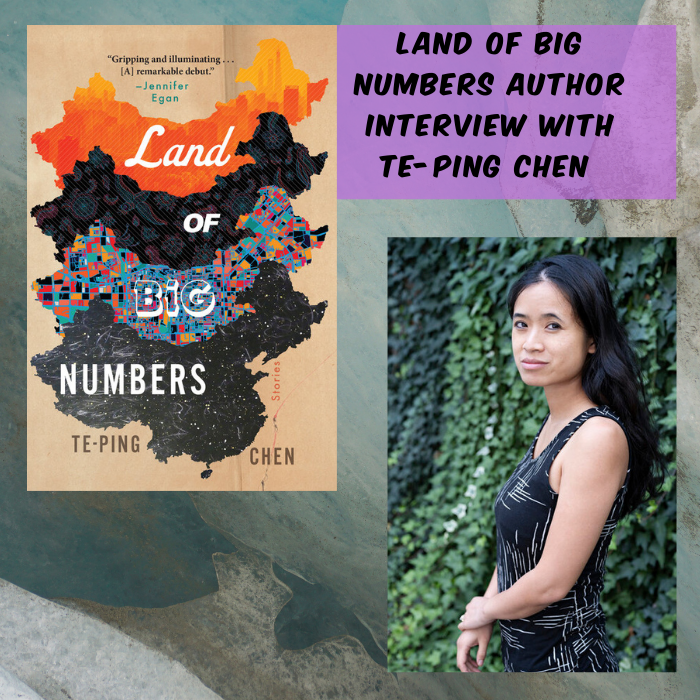

Land of Big Numbers is a collection of short stories written by Te-Ping Chen who is a journalist with the Wall Street Journal. Drawing on her experience of living in China, Chen creates a portrait of how everyday life in China looks like as well as its diaspora. The stories also show the social, political, and family life in China while also discussing issues of an authoritarian government, multi-generational families, and relationships on the personal and the community level. The stories are both realistic and magical and the collection has quite a few vying to be the favorite. I interviewed Chen on her inspiration behind this collection, her time in China, her favorite stories, her reading, and her advice for writers.

RM: When did you first realize that you want to be a writer?

TPC: There wasn’t really any particular moment. I always loved to read and write but never thought it was possible to write for a career until I discovered journalism. Journalism felt like something that I could pursue and get paid for and maybe make it into a career. I loved discovering new things, the sense that you could let your curiosity guide you, meet all kinds of extraordinary people, and try to understand how the world works. For me, it was a little like having a lightbulb go on, and I felt that this was something that I could do.

RM: What inspired you to write this collection?

TPC: Sometimes, when things go unarticulated, that can start to feel like a heavy thing, especially in the context of my life in China, in which I was often talking to people who were exposing themselves or making themselves vulnerable in talking with a reporter. It felt like a tremendously privileged thing to be a journalist there, but not everything was a news story. For me, writing these stories was a way of also trying to capture life around me that didn’t fit into headlines, all these moments, stories, and fragments that I had been collecting in my head, and trying to give them life and release them onto a page. It has been extraordinary to see how readers have been responding, and I am really grateful for that.

RM: How did your background as a journalist for Wall Street Journal connect to writing this collection?

TPC: I was in China with the Wall Street Journal for a number of years but had initially moved to the country in Beijing in 2006 as a student. Although I was writing about China for my job with the Journal, it always felt like there was more to tell. When I started writing Land of Big Numbers, it was with the realization that I could still write and observe and capture and translate, but in a different context. Fiction became that vehicle.

RM: Where do you get your ideas? You were born in California and you lived in China for the study abroad program and as a reporter. How does your experience of living in two countries affect your stories?

TPC: The book is set mostly in China, and it’s those landscapes and locales that really shaped the stories. At that point, China was where I had spent a large portion of my adult life. At the time that I started writing these short stories, it felt like China was the place that I was most immediately familiar with. The experience of spending day in and day out and talking to people and trying to understand how the country works as a reporter was absolutely what most helped shape and influence these stories.

RM: Which is your favorite story and why?

TPC: I would probably say my favorite was “Flying Machine.” It’s about an inventor who tries to invent an airplane, even though he’s never flown. I loved writing that story–for me, it captures a part of the country that’s so special, the kind of character and person that you often encounter in China, resilient and resourceful. The main character, Cao Cao, is an ambitious dreamer who has this incredible spirit and ability to see things that are possible even though other people might not. I loved getting to write all the other elements in that story, from noodle-chopping robots to funeral strippers, bits and pieces that I had reported on in my time with the Journal in Beijing, but it felt like in that story I got to much more fully bring to life the world behind them; it was a treat for me to write.

RM: “Field Notes on a Marriage” and “Beautiful Country” are about Chinese American relationships. Was it a goal of yours, in this collection, to educate your audience about the common people in China?

TPC: I was really writing these stories for myself, not with the thought or expectation that anyone else would read them. So there wasn’t any didactic impulse behind writing these stories. That said, since the book has come out, I have been really happy to hear from so many readers about how powerfully they’ve related to the characters, even if the milieu might be unfamiliar to them. In reading Land of Big Numbers, I absolutely hope that people come away with a deeper understanding of the country and its people. I feel especially lucky to write the book when I did, and to live and report in the country when I did, given how so many reporters have since been kicked out of the country.

RM: There seems to be a preoccupation with multi-generational families, the figure of the outsider, and people under a repressive government. Why is that?

TPC: Land of Big Numbers is about a lot of different themes, and I think about it as a book about striving, in some ways — what it’s like to make a sense of identity for yourself in a place or circumstances that often feel out of your control. There are also stories that are about the friction that happens in the process, often in the context of families. Family is the crucible where people are formed but also bring their own radically different perspectives, and in several of these stories, you see those fissures between generations.

In terms of politics, that of course sculpts and shapes peoples’ lives in really strong ways that I wanted to capture. It’s such a central component of life in China, and maybe because of that, I think it’s a hard thing to fully render. When we talk about politics, it tends to be at a high level. In these stories, I was trying to bring the readers closer to a sense of what it might be like to grapple more intimately with some of the choices that come about while living in an authoritarian society like China, in which political questions also become deeply personal ones.

RM: How did you manage the various styles in the stories- realism with magical?

TPC: Some stories, like “Lulu,” which starts the collection — the one about the pair of twins, one who becomes a professional video gamer and the other who becomes an online activist — are told in a very straight, realist style. As a journalist, the realistic style comes very naturally, but at the same time, China is a country of such extremes that it can feel like life borders on magical realism anyway, in which you’re in this sometimes liminal space, where anything can happen, and so magical realism became a way of capturing that for readers, too. So in one story, readers see a neighborhood transformed by a fruit that has supernatural properties, forcing people to grapple with buried memories (“New Fruit”), and another, “Gubeikou Spirit,” has an almost dreamlike quality, in which these subway commuters are stuck underground for months on end. Some of this surrealism is partly a way of exploring philosophical and political questions — like what are the ways we see human characters refract and respond to the extreme, sometimes absurdist situations? But again, given what it can be like to live in modern-day China — a place where the government controls the weather and decides when to make it rain — day-to-day life already feels like it’s made up of details you couldn’t make up if you tried. Realism mixed with magical realism is a lot of what modern-day life in China can feel like.

RM: What do you like to do when you are not writing or reporting?

TPC: A lot of reading, spending time with family, and cooking. In China, it was also a lot of traveling and exploring. For much of the time that I’ve been back in the US, we’ve been in a pandemic. I’m still figuring out what rhythms will be like with life on the other side.

RM: What books are you currently reading? Which authors inspire you?

TPC: I just finished The Last Exiles by Ann Shin which is set in North Korea, and also Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro. In the short story genre, some of my favorite authors are Carmen Maria Machado and Lesley Nneka Arimah. When I was writing this collection, I was reading a lot of Jhumpa Lahiri’s work. Another short story writer that I really love is Maile Meloy.

RM: What advice do you have for writers?

TPC: My advice is always to read. What has helped me the most has been reading, finding voices that I loved, and learning from them. Reading widely and trying to establish your own sense of taste and preference in ways that aren’t diluted by other people. I think it’s important to identify what works for you. I know there are times that when I read things, I didn’t respond the way other people or critics reacted to certain works, and that could be alienating. As I developed more confidence as a reader, I think that helped me as a writer as well.