One of the amazing parts of being a part of Feminist Book Club people will tell you, isn’t about the books. It is about the community that is built between the members and authors. In early December, FBC Members had the opportunity to discuss Braiding Sweetgrass, our November book of the month, with the author, Robin Wall Kimmerer. The discussion was raw, poignant, and cathartic at a time when we are all looking for hope and solutions to the biggest problems surrounding us. Below are some highlights from our conversation. We hope you’ll join us in January for our discussion with Roxane Gay, author of Difficult Women.

The Discussion

FBC Founder Renee: What is it about ecological justice that makes it a feminist issue?

Robin Wall Kimmerer: The rise of feminist voices and leadership in the tradition of conventional male leadership has made ecological justice a feminist issue. Also regenerative economies and communion of the earth as the divine feminine. The primacy of the relationship between women and the land is important.

Nora L.: What daily act of personal reclamation and reciprocity are you still taking part in? Are there new lessons from the earth and ancestors that you’d like to add to the book or perhaps in a new book?

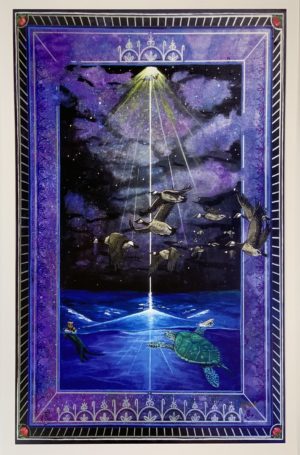

RWK: I am now involved in a project to plan an experimental climate change forest. Soon, sugar maples will become climate refugees. We are carefully planting species that are native and abundant, so that when changes become extreme, other pants will know about these trees and have a relationship with them. There is a new commemorative edition of Braiding Sweetgrass with artwork and a new introduction that acknowledges that I wrote the book in a more innocent time. This new version includes a part that grows from the Sky Woman story. Knowing how much women can change the world, I ask the question – what if Sky Woman jumped with full agency to change the world. “What does it take to jump to a new world?”

Katie: Can you elaborate on your experience as a woman, and particularly as an Indigenous woman in academia? I’m curious what your experience in the academy, which is known to reject atypical viewpoints in the biological sciences, has been like.

RWK: I was the second woman in the entire university to join the faculty. It has not been easy and can be really isolating as science is super masculine. I had set put clearly what I would do; I would not be enmeshed in the same game that male academics were playing. I was intentional about my path in academia rather than fit into other’s expectations. It was not easy but the rewards at the end have been immense. The old guard folks did not want me present. I would say to claim your space and do it according to the things that you value. Create a pathway for yourself rather than be assimilated into a culture that does not fit your values.

Steph A.: You write, “Can America, as a nation of immigrants, learn to live here as if we are staying?” You later point out that immigrants cannot by nature be Indigenous but can become naturalized. How can we move toward a relationship of reverence and reciprocity? Do you think this is something we can still learn? How?

RWK: All of us here are talking together right now. People find each other and choose to see the world as gift more than seeing the world as commodities. We need to lead a simpler life, and live as if we are staying and have to have land available to give to our children, and their children.

Stephanie One: The concept of a gift economy and reciprocity really resonated with me. In a country so rooted in capitalism and this mindset of scarcity, how do make a change that will shift us closer to a gift economy on a larger scale?

RWK: Scarcity is a part of the whole market economy as opposed to real scarcity in the world. The capitalist economy can be obscene in its large-scale production and this violates ecological norms. We can’t create a gift economy on a large scale but we can evolve and work towards it on a small scale. Invest in neighbors and communities where reciprocity can work.

Rashmila: How do I incorporate your teachings as a person who lives in the city with very few connections to nature and limited resources? I do practice gratitude and the things you discuss in chapters “The Honorable Harvest” and “Sitting in a Circle” but I don’t think that’s enough.

RWK: Express reciprocity in and where you live in the city. The Honorable Harvest applies and reciprocates the things that you consume. We honor by not wasting and by sharing what we have. Asking permission about consuming- should I be buying that? Winter is upon us and we can access fruits from all over the world. However, think of the carbon footprint. Apart from conscious consumption, not wasting, and sharing, we can also indirectly reciprocate by voting, raising conscious kids, supporting local land trusts, parks, and community gardens.

Another Stephanie: In the Three Sisters chapter, you talk about how individuality is cherished and nurtured in your people’s culture. A lot of the problems in American society today are often chalked up to Americans being too individualistic so I’m curious what you think we’re missing that would make individualism good for society.

RWK: One of the elders said that we should write a Bill of Responsibilities instead of a Bill of Rights. There is a non-interference in who you need to be. This will be coupled together with responsibility and the gifts that you are given. So, we are distinctive and sovereign as individuals but we are also interdependent [with each other].

FBC members Kori and Julie: How we can repair and build a relationship with the land while not culturally appropriating the lessons, ceremonies, and rituals of the people whose stolen land we live on? How do we navigate the line between learning from Indigenous wisdom and trying to embrace it in my life, versus cultural appropriation?

Robin: Western culture lack rituals and ethics of connection, of praising the land, and reciprocity. So, it appropriates Indigenous traditions as they are not present or strong in Western beliefs. Ceremonies come from authentic connections to land, gifts of reciprocity to the land, creating our own relationship with the land, and both lived and ancestral experiences with land. We need to practice making such ceremonies. You can’t do it just like that, it is then cultural appropriation.

Natalia S.: I see stores that sell herbs for rituals that also sell sweetgrass. Would I be part of the problem if I bought sweetgrass because I liked the smell from one of these shops? I’m thinking of the story of the Spirit Man who says that sweetgrass shouldn’t be sold when it’s used in ritualistic methods. How can I be a cool about everything and support Indigenous communities, without messing it up?

Robin: How can you show your support? Support Native artists with their own creations, not by commoditizing the things. Support cultural practitioners. Support Natives who have land-based rural economies, who care for the land, and who are not selling plants but selling time (going gathering, caring). Pay attention to the world, your backyard, and you will discover that meanings have power.

Sarah: I’m interested in how your book has been received among rural communities. I’m calling in from Buffalo, NY, and the suburban and rural areas around our city have been a breeding ground for white supremacy, especially recently. Have you had many conversations about your book in suburban or rural communities and what has that reception been like?

RWK: Are my neighbors more conservative? Yes. Most of them are respectful of difference and tolerant, if not embracing, of difference. In my own lived experience, I have not encountered white supremacy. The closest that I have experienced it in my own community is the dismissal of social justice as something that doesn’t affect my neighbors. They are not hostile but not productive and deeply problematic. There is a deficit in an urban setting. We can practice reciprocity and justice for land without having our hands in the land.

The Chat

More often than not with FBC Members, there is also a whole separate conversation happening in the chat box of our calls. The discussion there was wide-reaching and touched on local consumerism, but also privilege (of all kinds), red-lining and the creation of food deserts, acts of appropriation/appreciation, and how to incorporate being more mindful in our daily lives. We also realized that in many cases, we were already practicing rituals that honored the land around us without even knowing it. It was also recommended for everyone to watch the film Gather, which is “…a portrait of the growing movement amongst Native Americans to reclaim their spiritual, political and cultural identities through food sovereignty, while battling the trauma of centuries of genocide.”