Today we’re talking about Spirit Run by Noé Alvarez, the first ever cis-gendered male featured here at Feminist Book Club. This review is coming from a place of conflicted emotions, I’m not going to bury the lede. So let’s dive in shall we?

Book Summary

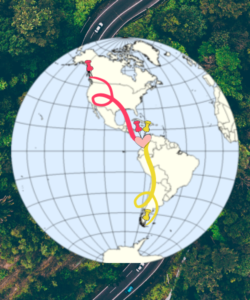

Growing up in Yakima, Washington, Noé Álvarez worked at an apple-packing plant alongside his mother. A university scholarship offered escape, but as a first-generation Latino college-goer, Álvarez struggled to fit in. At nineteen, he learned about an Indigenous/First Nations movement called the Peace and Dignity Journeys, marathons meant to renew cultural connections across North and South America. In 2004 he dropped out of school and joined the marathon.

Alvarez tells his story and the stories of the people he met during the marathon. He writes about things you’d expect, running, hunger, thirst, fear, parasites. He also talks about how he Indigenous and working-class humanity gets lost in a capitalist and colonialist society.

Let’s Have a Kiki

Let’s start with the positive, shall we? There were parts of this book that made me feel like I was a participant in Noé’s life. The descriptive language that he uses is evocative and almost poetic. It has a fantastic way of putting you in the scene with him.

There are bits that I can relate to as a first generation immigrant, even though my family’s immigration story is so different than his. Early in the book he writes, “Still, every day I try gathering words as our people do apples, ones to help keep me moving forward. Words that help me imagine what I struggle to imagine in this town. That I am worth something.” I underlined that in my copy and came back to it over and over again. Even today, as a thirty-something, I find myself looking for belonging in this country, never quite feeling like I fit in all the way. I imagine that this is common among the diaspora.

However, as I read the book I found myself frustrated with Noé as a narrator. When discussing his relationships with his family and friends he devoted more exposition, frailty, dimension and depth to the male voices around him. His mother seemed a caricature of a typical Latina woman. She made food, cooked, worked, and said things like “Eat more food son” or “Don’t be out late”. He allowed her one moment of human emotion when she separated from his father – but even then he didn’t allow her the opportunity to speak and give us her side of the story. I still can’t quite figure out what even happened between them!

When he’s on the run, this trend continues. He spends more time describing the actions, and potential motivations, for the behavior of his male counterparts. He mentions, much more briefly, the relationships he builds with women and their backstories but it seems like an afterthought. Is this because there were fewer women on a run for women? Is it because this kind of journey only attracted a certain kind of male person? I don’t know.

But is the book feminist Natalia?

I don’t think so. Certain women, but not all, have agency – some women only exist in the book as a reaction to the male counterparts. It’s problematic when viewed from this lens.

Ok, but what about the Peace and Dignity Journey itself?

The previous section was about the faults I perceived in Noé as a narrator. This part is where I reveal my faults as a reader.

…I do not believe the mortification of the flesh is ever necessary and it is through this lens that I am reviewing this part of the book which makes me a biased reader.

Simply put, I believe that real life is hard enough. It is hard for me to wrap my mind around making it harder for yourself to reach a state of rapture, ecstasy, or spiritual connection. I understand the theological pinnings behind it but I feel a secondhand, what’s the word, reaction? Empathetic suffering? An almost phantom pain when I read about what some religious traditions do to themselves in order to practice their faith.

Because of this – where I think some (most! If you look at the reviews on Goodreads and similar websites) read the Peace and Dignity Journey section and see something beautiful in it – I see unnecessary pain, both physically and emotionally. Noé details several instances of emotional abuse/bullying between different factions of runners. There were some who believed that pain was necessary, and made runners run an enormous amount of miles per day to show that they were “tough enough”, all while withholding access to water and food. When describing his very first run he says:

The runners have crowded inside the vans among the coolers, canned food, and other supplies.[…] They don’t let me on. They tell me that newbies run first and that those who don’t wake up early enough run carrying their backpacks. “But how am I supposed to run?” I say. Nobody has explained this to me.

This is following being in a majority white liberal arts college, dropping out because he felt called to honor his Indigenous background, his parent’s sacrifices, and then he gets there and it’s …. this? Once he’s been with the group a few weeks and has run from British Columbia and crossed the border into Washington state he reflects:

Here I recognize the ways in which running is transforming me. Through it, I am inflicting violence upon myself and my body, submerging myself in pain like I did when working in warehouses alongside my other, so that I may control the turmoil within me. But unlike any other labor, running relieves me of the weight that I should become better than my parents, my people. I still don’t know that it is ok to be unexceptional, ordinary, unremarkable

Over and over again, the language around the run is frank in its description of how hard it is, but it crescendos into a larger through-line that this pain is worth it. It’s a way to connect with ancestors and their forced migrations and honoring that journey. But I can’t help but wonder, if your ancestors endured the privations, dehumanization, and abject horror of a forced migration and you are alive to tell their story – does the act of desecrating yourself in this way to honor that sacrifice? There’s no right or wrong answer to this question. It’s subjective and can only be answered on an individual level. The answer changes from moment to moment even with Noé as he goes through the journey.

So…would you recommend this book?